by Michael Uhll & Caroline Alkadi

COVID-19 instigated an existential crisis of work. For millennials in particular, it accelerated the already existing disillusionment with work culture in the United States. When layoffs and furloughs hit at the onset of COVID, the millennial unemployment rate skyrocketed. According to Pew Research Center, 35 percent of Americans ages 18–29, and 30 percent of those ages 30–49, said they or someone in their household had lost their job since the beginning of the pandemic. In addition to bemoaning the economic burden of generational underemployment, millennials lament the alienation that has come to permeate our work lives, as evidenced by a slew of headlines in various publications towards the end of last year: “What is the Point of Non-Essential Work?” asked Marie Solis for Jezebel, while Clio Chang dubbed millennials“The Generation Shaped by Layoffs” in a Medium post. Editors at New Republic put it more simply: “Work Sucks.”

In 2021, gainful employment is not only rare and precarious; it feels largely meaningless, especially in the white-collar echelon to which many highly educated millennials aspire. Worried about their job prospects, everyone interviewed for this story requested that we not list their full names. We chatted over Zoom on a rainy March afternoon with Jon, a journalist from Chicago who was laid off at the beginning of the pandemic, to parse his feelings on the subject.

“It’s all alienating!” he explained. “I’ve always had entry-level jobs in offices. I’d rather have a job that directly helps people. Honestly, I liked working in the service industry for that reason. Even though it generally sucks, it does feel good to make someone a drink or give them their meal. It's not solving any big systemic issue but it feels good to give someone something."

But what if, in its own small way, this direct kind of work was solving big, systemic issues? Historians and amateurs alike have been struggling to find a precedent for our current labor crisis. While not a direct analog to today’s situation, Depression Era America is, in many ways, an apt one. We find ourselves in a similar economic condition, searching for solutions while our faith in contemporary institutions fades rapidly. The solution to both millennial malaise and the current economic downturn may lie with a long-dissolved New Deal agency.

The Works Progress Administration, a pillar of Roosevelt’s New Deal, directly employed Americans to work on infrastructure and arts projects across the country. A careful study of the original WPA could serve as a model for addressing today’s work crisis while laying the groundwork for a re-invigorated social state that has been decimated by decades of free-market reforms. A new WPA would also offer a unique opportunity to bridge economic, racial, age, and gender divides. While the original program may not have been intrinsically racist, only 15 percent of WPA workers were Black. With a focus on diversity & inclusion, a 21st-century model would not only spur economic growth via increased employment; it could serve as an equalizer too.

In 1935, the year the WPA was founded, the unemployment rate was over 20 percent. The program, along with Roosevelt’s other New Deal initiatives, was wildly successful almost immediately and helped bring unemployment down to 16.9 percent by the end of 1936. Between 1935 and 1943 (the year the WPA was disbanded), the program would employ over 8.5 million people. But economic aid was not the sole purpose of the administration, even at its onset. In a speech on March 21, 1933 announcing his proposal for a Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps (a program similar to the WPA that focused on rural areas), Roosevelt stated, “I propose to create a Corps to be used in simple work… More important, moreover, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work.” Who today could use the phrase “moral and spiritual value of work” with a straight face?

Highly educated millennials often opt in to relatively mindless desk jobs directly after graduating from higher institutions of learning, a society-mandated choice that further contributes to a work culture rife with disenchantment. “Once you start working at these huge firms, you realize that most everything you do is literally made up,” a recent college graduate working in the oft-mentioned, rarely understood consulting industry told us over the phone. “You’re just helping corporations get richer. I don’t really take pride in the work that I do, apart from my peers knowing that I make a decent amount of money.” Often, college graduates end up questioning if a degree was necessary; many end up stagnant in fields, unsuited to their interests and skill-sets.

After two largely depressing conversations with our white-collar cohort, we spoke with our friends Erika and Ezra, both recent graduates of Vassar College who live together in Brooklyn. Unlike most people we know, the couple has largely managed to avoid the oppression of a cubicle: Ezra has spent his post-grad years alternating between barista, farmhand, and art handler jobs, while Erika works at a healthcare non-profit. After several drinks in their homey Crown Heights apartment, however, it became clear that their alternative career choices have not put them at ease with our contemporary culture of work.

“My whole life, it was, ‘you’re gonna go do your best in school so that you can go to college,’” Ezra said. “And then I got out of college, and most people I knew got jobs through family connections, and I was just working restaurants and doing random gigs here and there. It’s been kind of tough, and it was hard to find good work even before COVID.”

Erika nodded in agreement. “It's sad to hear him say that, because honestly I like my job,” she said. “But I know why I like my job: My organization gives me a lot of agency with my time, I don’t do a lot of unnecessary work, and I have a task to be doing, and I know what it is, and I want to do it. I’m fortunate because it seems rare to feel that way.”

The WPA was divided into two subsets: construction and non-construction projects. The significantly larger construction division employed about 2.65 million of the 3.3 million workers on the WPA payroll at its peak in 1938. The program mobilized its workforce to an unbelievable degree: By 1943, it had constructed or made renovations to over 2,500 hospitals, 5,900 school buildings, 3,000 dams, 78,000 bridges, 1,000 airports, more than 10,000 public parks, and 650,000 miles of rural roads, sidewalks, park trails, and urban streets.

So how could we translate this into a workable model for the present crisis? As it turns out, our peers had an appetite for the kind of work that the WPA prioritized during the New Deal. When we asked Ezra and Erika where they thought the federal government should pool its resources, they both replied instantly: “infrastructure.” As it turns out, our current infrastructure is due for an upgrade. The American Society of Civil Engineers recently gave it a “C-,” citing endemic water main breaks, poorly maintained highways, and rapidly deteriorating energy grids.

Although the federal WPA sponsored a number of projects on a national scale, the original project’s implementation strategies were remarkably grassroots. Cities and municipalities determined their communities’ needs and levels of unemployment and sent proposals for projects to the state WPA office. These proposals were then forwarded to the national WPA, which either approved or denied the funds. This process allowed priorly unemployed Americans to work where they lived while receiving their paychecks directly from the federal government. Similar projects today would alleviate our generation’s growing professional detachment by letting millennials work in and feel connected to their own communities.

“A good project could be, for example, getting unemployed young people to build and then staff grocery stores in urban food deserts,” Erika suggested. “There are already tons of people in those communities who need jobs. Why not just have the government directly fund that?”

Jon took this idea one step further in his interview. “The country, like the world, needs solutions to climate catastrophe, which means we do NOT need more selfish tech giants, or technology 'disruptors', or corporate power,” he said, emphasizing his words with frustrated hand motions. “We need more gardeners, more labor activists, more people fighting for land and water rights, more equitable technology, less capitalism.”

Ezra suggested putting more resources and labor towards converting the nation’s energy infrastructure. “There’s a lot of people doing the ‘science’ part of that, but not enough people actually mobilizing to make it a reality,” he said.

The idea of a “Green New Deal” based on Roosevelt’s original model has circulated among progressives in the last few years, and the official proposal even made it to the House floor in 2019. (It was, like all halfway decent legislation during the Trump years, rejected in the Senate.) Almost daily, our push notifications remind us of the urgent necessity for this kind of environmentally inclined, structural upheaval. The fires in California last year showed the need for denser, more environmentally informed real estate development, and the recent blackouts across Texas emphasized the dire need for climate-minded upgrades to our power systems.

Somehow, over the last few decades, the idea of a ‘good’ job became synonymous with inflated pay and mindless emailing. These positions are not only demoralizing; they fail to address the country’s most pressing needs. Thankfully, there seems to be a growing milieu of restless millennial workers anxious to find a purpose in the work they do.

“Working and building on the land is a way to bring about justice, if done in the right way,” Ezra said, offering the example of solar panel installation. “I think it would make me feel better, compared to the jobs I’ve done before."

Jon, on the other hand, said a career in a creative field would help him feel more fulfilled. “Writing, gardening, reading,” he speculated. “I’m not sure, I guess. I feel most connected to work when I am learning or helping someone, so something along those lines. I want to work and speak directly with people, rather than over email!”

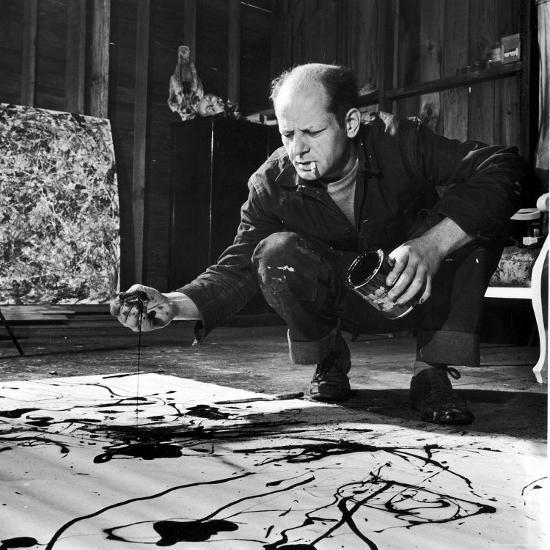

The original WPA also provided a model for workers with creative skill sets. Federal Project Number One, a division of the WPA, managed professional and artistic programs. The project’s arts components were divided into five subsections: hiring musicians as school teachers, funding public concerts, hiring actors to stage productions throughout the country, commissioning artists to paint public murals, and hiring writers to record regional folklore and oral histories and publish community business and travel guides. FPN1 also created the Historical Records Survey, which sent unemployed librarians, researchers, and writers to index state and local archives. In the arts alone, annual spending for WPA-sponsored projects between 1935 and 1943 amounted to $1.6 billion, adjusted for inflation. In those years, it made up 5 percent of the annual federal budget. Today, the annual budget for the National Endowment for the Arts sits at $155 million, 0.004% of the federal budget.

We spoke with our friend Niccolo, a graduate of Pratt Institute, about working in the arts today. He started his career as a graphic designer at Calvin Klein and Document Journal, before going freelance and collaborating with brands like Red Bull Arts and Solid & Striped. He expressed a desire to connect with a community to give his work purpose. “Community is what I think about most when considering potential jobs,” he said. He is interested in teaching, but has found there is little opportunity.

Some of the most famous American artists and writers—Mark Rothko, Richard Wright, John Steinbeck, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston—began their careers at the WPA through FPN1. Ellison credited his WPA oral history projects with helping him develop the colloquial prose of Invisible Man. Steinbeck paid similar homage to the program in the introduction to his 1962 travelogue, Travels With Charley, stating that the folktales transcribed by WPA writers were “the most comprehensive accounts of the United States ever got together… compiled… by the best writers in America.” FPN1 was disbanded in 1939 over fears that it was fomenting communism in its ranks and promoting “racial mixing” in southern states.

Nowadays, those who once would have chosen to pursue careers in the arts, academia, or media find these paths economically infeasible or, at least, not worth the significant salary gap. The WPA legitimized a broad spectrum of skills as dignified labor worthy of direct government aid, from building physical infrastructure to education to arts production. Construction workers, teachers, health care workers, artists, writers, academics, and musicians were all deemed equally worthy of direct government investment and fair compensation.

Today’s anemic, profit-oriented social state is a far cry from that ethos. “People who want to be artists with a capital 'A' have to do it themselves or have a solid amount of emotional support from their families,” Nico said.

The original WPA proved that paying people to hone their skill-sets and do what comes naturally to them for employment wasn’t a pipedream; it was an effective way to maximize the labor force. It was radical that the federal government was directly paying writers, artists, actors, and educators. And it’s still radical today to imagine millennials not having to choose between their crafts and living wages. A new WPA would reinvest in our nation’s infrastructure, but it would also pay artists to revamp public spaces with installations, writers to capture the mood of our time in print and record people’s stories, and musicians to play public concerts. It would reestablish the importance of the social sciences, fine arts, and humanities via increased federal funding for tenured faculty positions at public universities, giving academically inclined millennials clearer career paths. The COVID crisis has given us time to think about the changes we want to see in every facet of our society. Why not reimagine work?

Caroline Alkadi works for a design studio. Michael Uhll works for the New York City government. Both live in Brooklyn. Get to know them better: @tuuuski and @therealmikeyrocks

*Thumbnail image: Vera Block's "Work Pays America!" poster (c. 1936-1939), commisioned by the Federal Art Project.