by Lily Houston Smith

Alcohol, for me, has proven itself time and again to be both a blessing and a curse. I am thankful for the many lasting friendships that began under its influence and the stories of drunken escapades that make me such a lively dinner guest. I am less thankful, however, for its ever-mounting costs—at once physical, psychological, and monetary.

Last January, I tallied up the proverbial (and literal) bill and decided enough was enough. I swore off alcohol altogether, attended a handful of AA meetings, and ended up spending seven entire months sober. (I even abstained from all my other favorite mind-altering substances, save for one cheeky marijuana cigarette on a trying evening in June.) It was the longest stretch, by orders of magnitude, I’d ever managed.

Over the last year, alarming statistics have been cropping up, and scientists have been urging officials to lower recommended daily alcohol consumption in federal dietary guidelines. Heavy drinking is on the rise—as are overdose deaths and rates of depression and anxiety. As a brand-new teetotaler, I felt myself exempt from all the worried predictions of public health officials. Alas, sometime in July, I was offered a jalapeño margarita and relented. By New Year’s Eve, I was a whole bottle of wine deep, doing whippets out of a party balloon, and wondering if maybe it was time, once more, to assess.

During the brief course of my sobriety, I found enormous solace in memoirists—Caroline Knapp, Elizabeth Wurtzel, Carrie Fisher. I looked into their texts as mirrors, searching for the parts of myself I could recognize. And there it all was: the physical, psychological, monetary damage—the powerful, unruly joy. Compiled here are just some of the titles I’ve begun to stack on my nightstand as Dry January draws to a close, and I begin to contemplate what I want the rest of this year—and this life—to look like.

Nothing Good Can Come From This: Essays by Kristi Coulter

I’ve read dozens of addiction memoirs, and most of them center on the drama of active alcoholism—the fights, the blackouts, the careers and relationships left shattered—and gloss over the lonely, tiresome process of getting sober. This makes sense, for someone trying to package a story that can be marketed and sold. Life, as it turns out, can get pretty boring after a person stops fucking up.

Coulter’s essay collection proves this needn’t always be the case. Funny, hard-hitting, and utterly delightful—this slim volume offers short, chewable essays that allude to, but don’t zero in on, the tumultuousness of being a heavy drinker. Rather, Coulter marinates in the complex flavors of life after alcohol—the little absurdities, the petty frustrations, the laughter. This collection is one I will return to every time I need a reminder that drinking is not the secret ingredient to a full, exciting, adventurous life—to intimacy or pleasure or fun. It is merely one ingredient that—Coulter argues—can be successfully substituted with countless others: spa days, home-cooked meals, meditation, binge-watching a season of your favorite TV show. Whether with a glass of red wine in hand or a seltzer with a squeeze of lime, life will prove itself over and over to be in turn excruciating, dull, and bursting at the seams with joy.

Sirens by Joshua Mohr

After you’ve read enough memoirs about addiction, you start to notice some patterns—like, for example, how many seem to read as a progression of war stories, which grow more impressively extreme from chapter to chapter. This can make for entertaining reading, but one starts to long for more depth—for some lesson to be gleaned beyond a vague sense that drugs are fun, but bad.

On this front, Mohr delivers. His impressively extreme drinking and drugging stories are paired with an equally impressive capacity to reflect on his toxic patterns of behavior, enough so that no matter how dark a place he finds himself in, we’re sure he can be redeemed. Published from one of my favorite small presses, Two Dollar Radio, Sirens is probably the least-read of the books on this list—which is a shame. It’s an absolute whack of uncompromising, compassionate honesty—a beautiful book not just about alcoholism and drug addiction, but about learning to be a father and striving to live up to one’s own standards of goodness.

Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget by Sarah Hepola

Published in 2015, Hepola’s bestselling memoir has become an instant classic in the canon of addiction literature—and for good reason. Blackout is a mosaic of careful self-reflection, meticulous research, and powerful storytelling. Hepola’s goal is not simply memoiristic—though she does search her past for insight into the alcoholism that would plague her into adulthood. She is also on a mission to understand the blackouts of her past. How do they happen? To whom, and why?

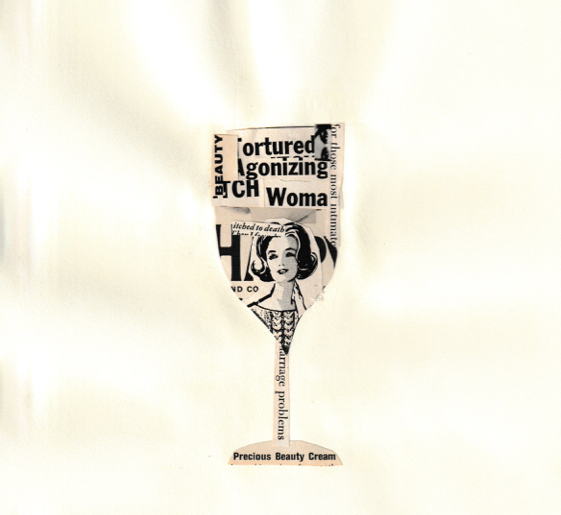

As it turns out, blackouts happen with more frequency to women, and are more likely to occur the fewer calories they’ve consumed pre-binge. Restrictive diets, aggressive partying, the urgent desire to project an image of independence, free-spiritedness, and fun all struck an eerie chord as I read through Blackout and recalled my own experiences blinking at dark, crowded parties and opening my eyes to empty, sunlit rooms. For Hepola, the disorientation of blacking out becomes more and more dizzying as the years wear on and she begins confronting—with increasing frequency and vividness—the horror of living so much of one’s life in the dark.

The Recovering: Intoxication and its Aftermath by Leslie Jamison

The person I idealized most growing up was Carrie Bradshaw, which perhaps sheds light on my myriad romantic failures, as well as my eventual decision to be a writer—and a writer who drank. The creators of Sex and the City (almost) never portray Carrie’s constant stream of cocktails as a problem, so much as a symbol of her glamorous independence.

The archetype of the writer as drinker is an age-old cliché with origins far earlier than Carrie’s on-screen debut in the late nineties. Hunter S. Thompson, Jean Rhys, Ernest Hemingway, Truman Capote—all important writers, all compulsive drinkers or alcoholics. Understanding this myth—and attempting to dismantle it—is the ambitious goal of Jamison’s hefty tome, The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath.

In her typical fashion, Jamison intertwines literary and cultural criticism with memoir to tell the complex story of her troubled relationship with alcohol and eventual decision to get sober. It is also a deep dive into the addiction recovery practices made popular by Alcoholics Anonymous. (Her thoughts on the topic were my primary inspiration to put hesitation aside and attend meetings, which I did up until the pandemic forced members to meet virtually.)

One popular critique of Jamison’s book is that her alcoholism is perhaps not sufficiently extreme to warrant a memoir on the topic. I find this critique offensive—an echo of the toxic, virulent belief that in order to deserve treatment (or an opinion), one must reach some arbitrary threshold of suffering or negative consequence. It is against this very thinking that Jamison writes. The only requirement, after all, for membership in AA, is a desire to stop drinking—or rather, one must realize, however reluctantly or skeptically, that maybe one’s life could be better if alcohol weren’t a part of it.

I have not been arrested or ended up in a hospital bed with a tube down my throat. But I, like Jamison, have found myself in strangers’ beds, on bathroom floors, at parties among tight-lipped, concerned-looking friends, wondering if perhaps this time I’d gone too far; wondering if the allure of glamor and adventure that Carrie’s twinkling martini glasses had always seemed to offer was a promise I’d been imagining all along.

Lily is a writer and audio producer living in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. You can see what she’s up to on Twitter: @Lily_H_Smith.