Written by Alex Bagenal Graphics by James Merritt

I’ve been reading about nematodes. Nematodes are very small, slender worms. They are pretty much everywhere. Our dying planet is alive with them. Teetering on the brink of a climate apocalypse, it is shrouded in a wriggly pall of nematodes. Truthfully, it’s not our planet: for every human, there are approximately 60 billion nematodes and they account for 80 per cent of all animal life on Earth. If anything, this world belongs to them. We are only its caretakers, and we are not doing a very good job of it.

There are lots of types of nematode: anything from 30,000 to 1 million individual species. The smallest are invisible to the naked eye, the largest – which live coiled inside the placenta of sperm whales – are about as long as a London bus. Many nematodes are parasitic; wherever there is an abundance of human or animal or plant life, there are lots of nematodes too. In 1914, Nathan Cobb – allegedly the father of ‘nematology’ – wrote:

if all the matter in the universe except the nematodes were swept away, our world would still be dimly recognizable, and if, as disembodied spirits, we could then investigate it, we should find its mountains, hills, vales, rivers, lakes, and oceans represented by a film of nematodes. The location of towns would be decipherable since, for every massing of human beings, there would be a corresponding massing of certain nematodes. Trees would still stand in ghostly rows representing our streets and highways. The location of the various plants and animals would still be decipherable, and, had we sufficient knowledge, in many cases even their species could be determined by an examination of their erstwhile nematode parasites.

It’s an unnerving thought experiment. Perhaps this is because it doesn’t require any transformation or addition, only the subtraction of everything that is not a tiny, slimy worm. The vivid netherworld which Cobb describes already exists, on top of, and around, and within, our own familiar world. It offers a sudden window onto a world which is entirely non-human and which, nonetheless, exists like a photographic negative, superimposed onto our own.

Thinking about the world in non-human terms can be both chilling and refreshing. In doing so we begin to approach the limits of human imagination. It’s important to remember that the world in which we live, and which we continue to endanger with anthropogenic climate change, plays host to a mass of strange animals and bugs.

Now this might sound trite, but I wonder whether thinking about nematodes might shine a light on our climate predicament.

The inhuman proportions of the climate crisis can be very difficult to get to grips with.

It is hard to imagine what human life will look like in 15 years, let alone 100. It is hard to imagine what it will mean when, in 2050, as many as 250 million people could have been forced from their homelands as environmental refugees by rising sea levels, droughts and desertification.[1] And it’s near impossible to imagine what the planet might look like if it were so ravaged by climate change as to have become entirely inhospitable to human life.

In this way, the climate problem becomes as much a crisis of imagination as it is a physical crisis. Our failure to imagine the long-term effects of the climate crisis is concomitant with our failure to imagine (or embrace) ways of solving it. There is no easy retreat from climate disaster. And yet, in the West, the political establishment continues to flirt with the idea that the issue might simply resolve itself: that we might, by making piecemeal modifications to our behaviour over time, gradually manage to extricate ourselves from the unravelling apocalypse. But this point of view is a luxury, fast becoming untenable, and, as the French political ecologist André Gorz wrote, “the essence of luxury is that it cannot be democratized.” [2] The gradualists are a dwindling class of elites, who are signing treaties and making (and breaking) pint-sized promises. And all the while the world is burning, each day brighter.

When compared with that of the nematode, human biological evolution is a pretty sluggish process. Because we develop so slowly, the average time between when we are born and when we reproduce – that is, the average length of a human generation – is between 20 and 30 years. And the average human fertility rate is only 2.5. Nematodes do it differently. Nematodes tend to have far, far more children than humans. The nematode lifecycle also tends to be much, much shorter. So, whilst only 3 generations of humans separate the discovery of the atomic bomb and the signing of the Paris Climate Accords, the same period will have played host to literally countless generations of even a single species of nematode.

Anthropogenic climate change is happening very fast. Maybe the nematode’s capacity to adapt to environmental changes will be its saving grace, maybe they will evolve biological coping mechanisms to survive the extremities of climate on our moribund planet. But we won’t. What we can do, though, is adapt culturally and politically. This kind of evolutionary adaptation has come quickly to us in the past, and we must have courage and fight to bring it about now.

I wonder, if we were to repeat Cobb’s thought experiment today, this moment, what we would see. Alongside the nematode mountains and trees and highways and houses, would we also see the seeds of our own destruction, preserved in spooky nematode form? Would we see, dimly, the dark silhouettes of coal and coltan mines, of oil fields, petrochemical refineries and industrial cattle farms? Would we see Wall Street and the City of London, and the offices of JPMorgan, HSBC and Wells Fargo, and all the stock exchanges the world over - all of these cathedrals and palaces of capital - outlined in a skin of wiggly nematodes? What kind of a grim monument to human achievement would this be?

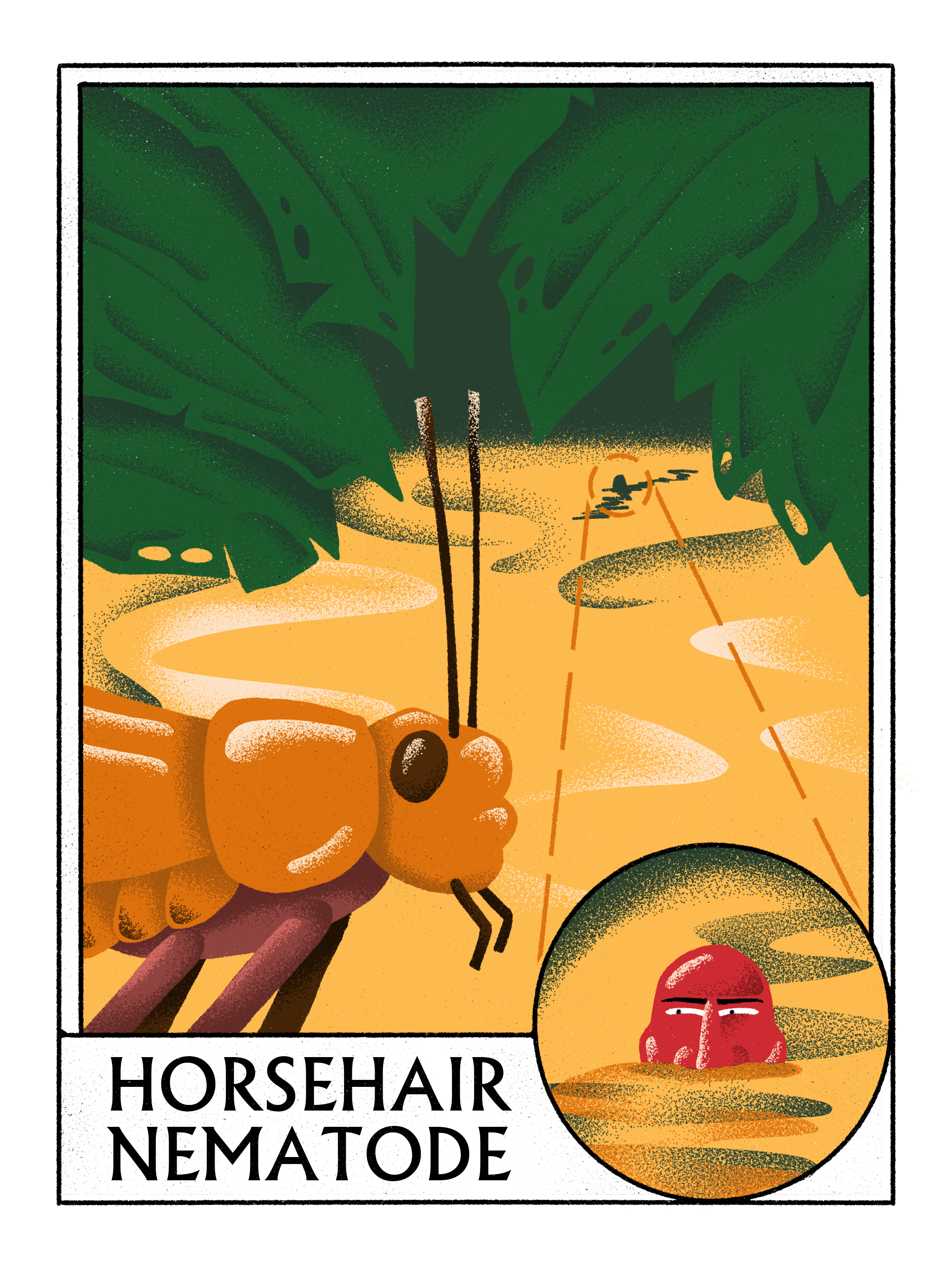

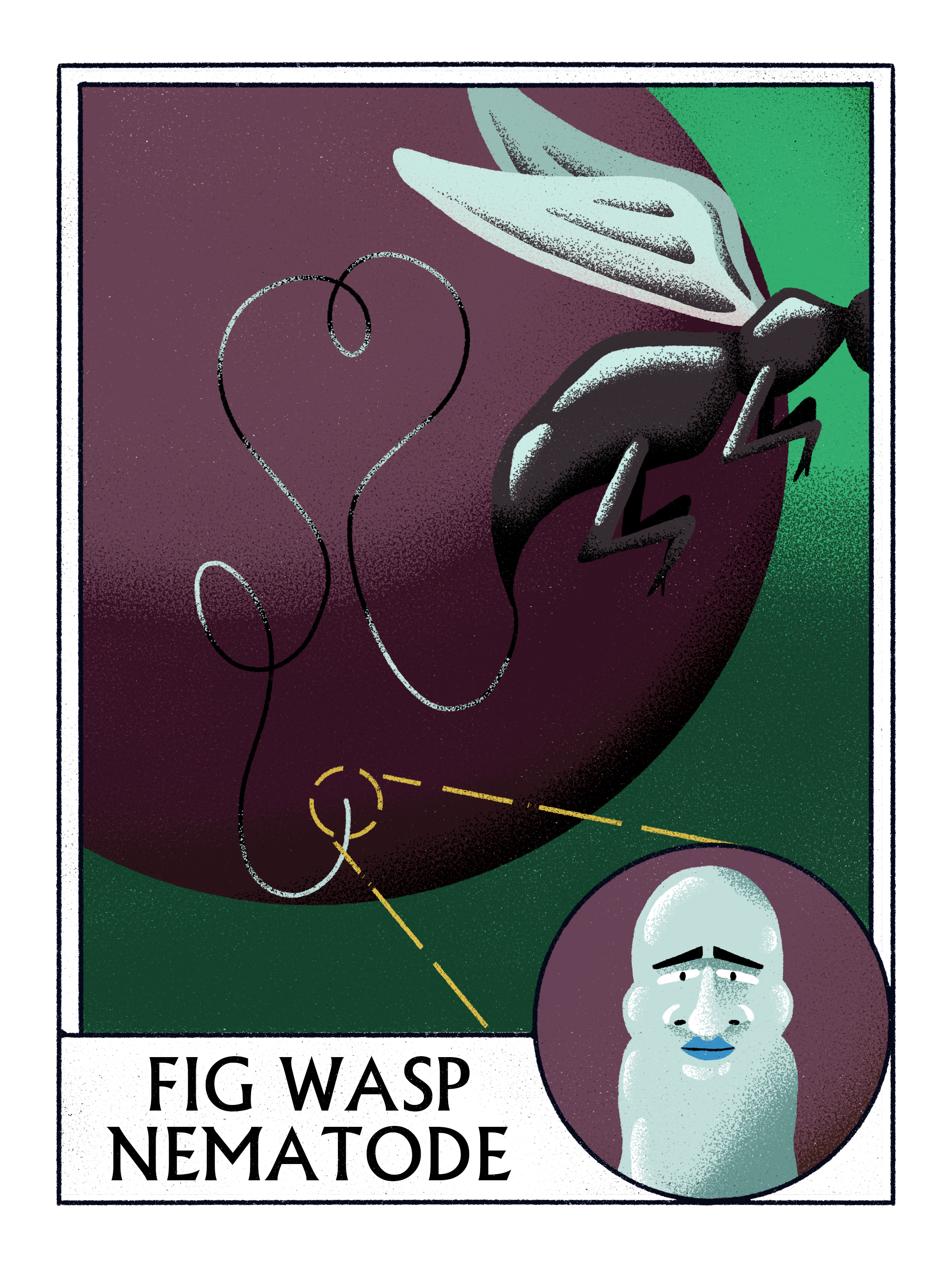

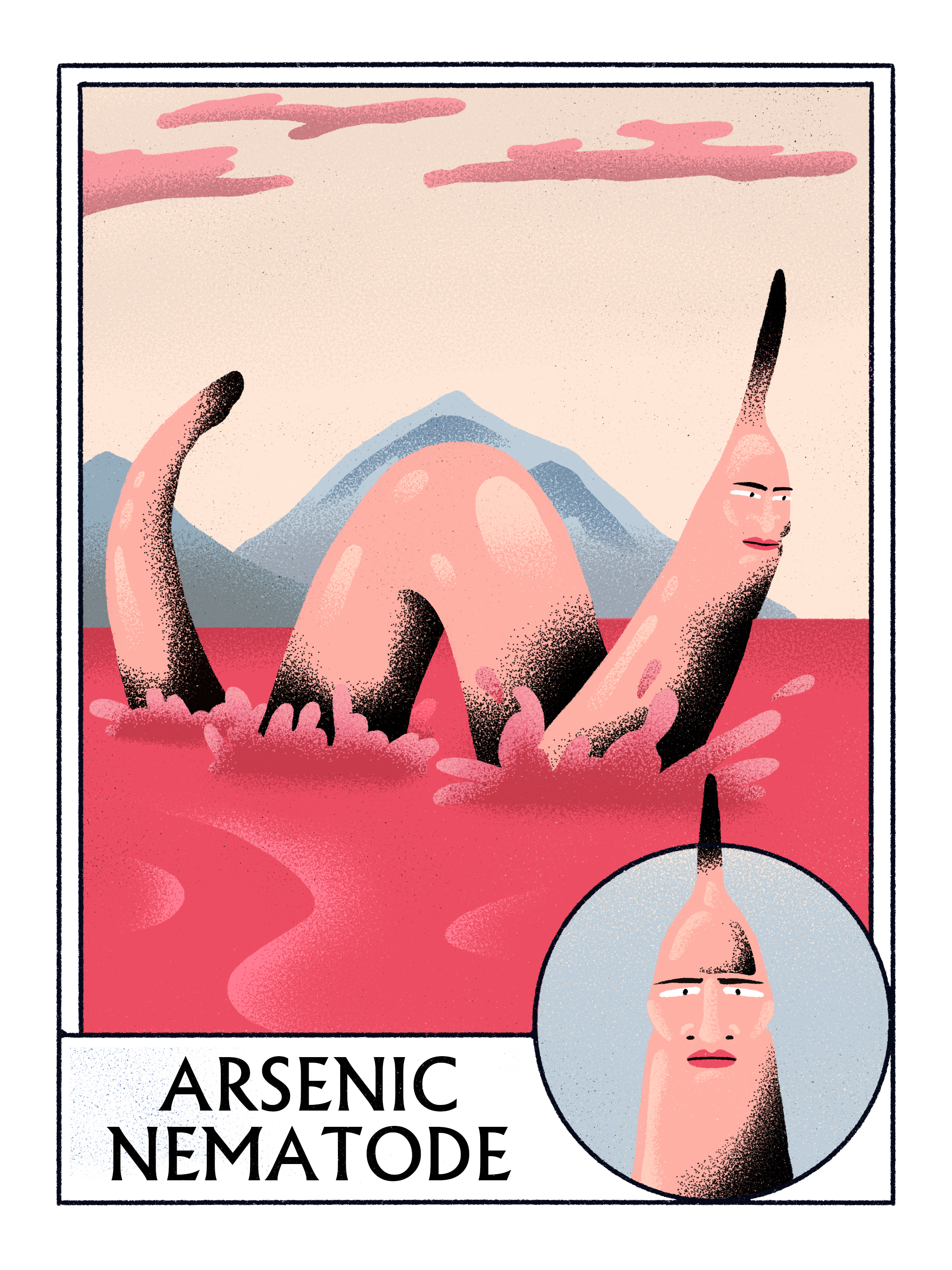

Choose your fighter / fuck, marry, kill:

Horsehair Nematode: Infects grasshoppers, crickets and spiders, filling the entire body of its host but leaving its vital organs intact. Induces thirst in the host insect, making it seek out and then jump into a body of water. The host then drowns, and the adult nematode emerges and reproduces in the water. Its eggs are ingested by insects drinking from the water and the cycle continues.

Fig Wasp Nematode: Preys upon fig wasps (which eat – you guessed it – figs). Rides the wasp from the ripe fig of its birth to the fig flower of its death, whereupon it kills the wasp, reproduces, and its larvae await the birth of the next generation of wasps as the succulent fig slowly ripens in the Italian sun.

Arsenic Nematode: Literally lives in arsenic and can survive 500 times the lethal human dose. Thrives in the inhospitably salty alkaline waters of Mono Lake in California. Has 3 distinct sexes and carries its young inside its body like a kangaroo.

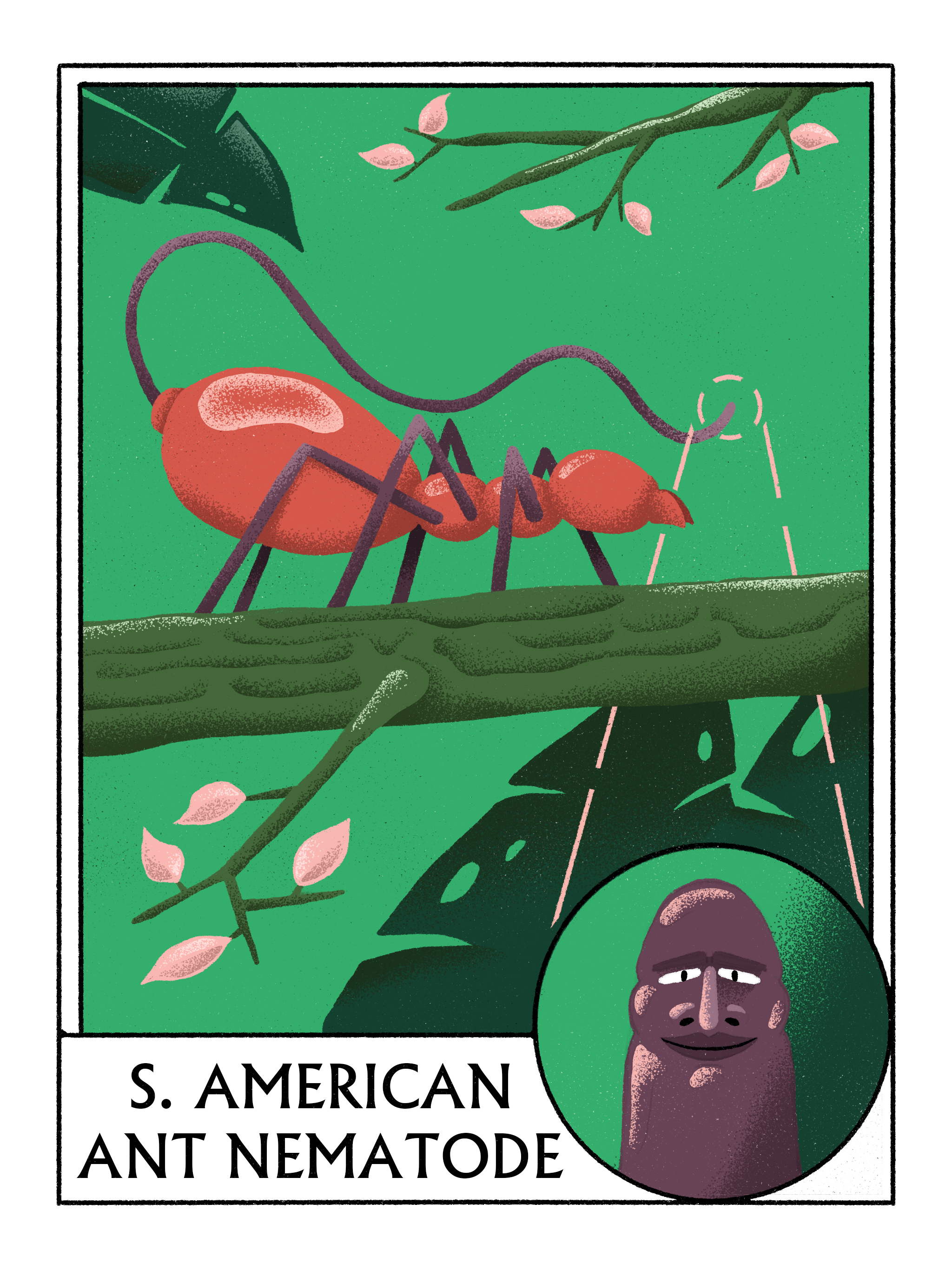

South American Ant Nematode: Begins life as an egg inside an ant. The egg hatches in the ant’s abdomen and the adult nematode reproduces (still inside the living ant), laying a new, bright red egg. The ant’s abdomen becomes translucent so that the new egg can be seen through its skin. The ant, running around the forest floor, is then mistaken for a delicious red berry by a bird and eaten. The nematode egg passes through the bird’s digestive system and the egg is defecated out. A passing ant notices the nematode egg in the pile of bird shit, picks it up and feeds it to its larvae, and the beautiful cycle of life continues.

OR… Choose your own from Facebook’s worm-based counterpart, Wormbook.

[1] Christian Aid, Human Tide: The Real Migration Crisis, (2007), p. 6

[2] André Gorz, ‘The Social Ideology of the Motorcar’, in Ecologica, Chris Turner, trans., (Seagull Books, 2010)

Check LONYC weekly our take on: politics, photography, food, fashion, film, music and creative writing. Follow us, feel the vibe @laidoffny.

Get to know Alex better, @alex_bagenal for all his latest intellectual endeavours.

For more thought provoking graphics check out @_jamesmerritt.