by Holly Devon

Before the assasination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse dominated headlines, Haiti had been growing visible in the news cycle for increasing political instability. On June 25th, an Al Jazeera headline read “Haiti gang leader declares ‘revolution’ as violence spreads.” Sourced from Reuters, the article concerns the escalating violence in the streets of Port-au-Prince which came to a head last Wednesday with Moïse’s death. The violence is largely attributed to the rise of Jimmy Cherizier and his “federation of nine gangs.”

The report echoes the mainstream media’s typical depiction of the island—one where machete-wielding gang members loot banks and supermarkets with impunity in the face of Haiti’s weakened government institutions. From the first sentence reporting Cherizier’s threat to launch “a revolution in the impoverished Caribbean nation,” to the last, the article reads like a grim prophecy for a nation destined for perpetual poverty.

If everything you know about the second oldest republic in the western hemisphere comes from the news, this story should sound more or less familiar. According to the news cycle, Haiti is one continuous disaster. From earthquakes and hurricanes to government corruption and election violence, each headline reinforces the truism so doggedly repeated by the press in report after report: Haiti is the poorest nation in the western hemisphere.

But for those of us who normally associate Haiti with its wealth, which is non-material and therefore difficult to quantify, reading about Haiti in the mainstream news is a constant source of frustration. There is no denying that the country faces considerable external and internal pressures, but the failure of the international press to place Haiti’s misfortunes in their global context strips the nation of the outsized power and influence it has held since the Haitian Revolution of 1791.

As Haitian scholar Patrick Bellegarde-Smith writes, “there is no possible divorce between the forces of globalism and Haiti.” The nation was forged in the fires of globalization as they first manifested in the plantation hellscape that reigned supreme over the 18th century. Colonial Saint-Domingue, which was the richest colony in the western hemisphere pre-revolution, provided the European continent with immense capital at the expense of enslaved Africans. The overthrow of the plantation by the enslaved began in 1791, and was solidified when Haiti’s first head-of-state, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, sent Napoleon’s army scampering back to Europe in 1803. During the revolution and afterwards, Haitians not only transformed a seemingly omnipotent power structure but completely redefined political power itself.

Haitian misery may move outsiders to pity, but it leaves them with no curiosity about an exceptional country that is nothing if not a force to be reckoned with. I remember once telling someone I was planning on studying Haiti in my master’s program, and they snorted in reply, “Why would you do that? Unless of course you like poverty.” In the case of this individual, the news cycle broadcasted its message loudly and clearly: Other than its underdevelopment, what is there possibly to learn about Haiti?

Anyone who expands their intellectual horizons just a few centimeters beyond CNN’s will quickly realize that Haiti has considerable perspective to offer the world around it. Unfortunately, professional journalists are ill-equipped to convey any of it, in part because the media appears generally allergic to historical context. The only background Al Jazeera offers for Cherizier’s declaration of ‘revolution’ is a link to a longer Al Jazeera article on the political crisis instigated by Haitian President Jovenel Moïse’s recent refusal to give up the presidency. But for any news source which includes the word “revolution” in a headline concerning Haiti, where revolutionary history remains a potent force, a complete omission of the Haitian Revolution is such a serious oversight that it amounts to a factual error.

Beyond the threat of gang violence, Jimmy Cherizier’s call for “revolution” is an appeal to Haitians' intergenerational understanding that political power is something that is never given. In consciously invoking the past as a way to impact Haiti’s political future, Cherizier’s power play acquires new dimension. Whether or not his political efforts are of long-term benefit to the Haitian people, or are being carried out in good faith, Cherizier is working with a political sophistication that cannot be seen unless he is framed within the historical discourse his revolutionary language engages.

Some alternative media sources do attempt to broaden the scope of the conversation from the margins by letting historians weigh in. In March, grassroots journalism website WeaveNews published an article by Jesus Ruiz, which places student protests in the streets of Port-au-Prince within Haiti’s tradition of popular resistance. Ruiz lists plantation slavery, French colonialism, invasion by the United States Marines, and former Dominican president Rafael Trujillo’s genocidal campaign against Haitians as fierce opponents in Haiti’s centuries-long battle for political and economic autonomy, without which their current predicament can’t be understood.

The Conversation recently published an article by Marlene Daut, who directly ties Haitian poverty to Western policies. Armed with the brutal historical facts, Daut calculates the cost of the crippling indemnity French gunboats forced the Haitian government to pay in compensation to French plantation owners for their human property losses after the revolution. If the country hadn’t spent 122 years hemorrhaging billions of dollars at the hands of French extortionists, Haiti might well be in possession of a prosperous economy today.

In another Conversation piece, Julia Gaffield identifies the role of Haitian founding father Jean-Jacques Dessalines in contemporary political protests, where everything from his portrait to protestors dressed as the man himself have been sighted in the streets of Port-au-Prince. By explaining the life and times of this singular historical figure, succinctly summarizing Haiti’s new political crisis from the earthquake to present day, and indicating how Dessalines fits into the picture, Gaffield deftly proves that journalism and history needn’t exist in separate worlds.

These historians help us see Haiti in its full complexity by giving us a wider lens than journalism typically does. They demonstrate that the island nation has been relentlessly fighting the global capitalist power structure for three hundred years, and that anything that doesn’t place the country within this context is bound to have a skewed perspective. In the words of Haitian radical historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “We are never as steeped in history as when we pretend not to be, but if we stop pretending we may gain in understanding what we lost in false innocence.”

Then again, we shouldn’t presume that false innocence is something the establishment press is prepared to lose. A closer look at the opinion sections of America's newspapers of record suggests willful ignorance founded on intractable prejudice. The mandate of objectivity under which reporters are obligated to labor generally prohibits the expression of explicit bias, but editorials don’t have that impediment. The latest batch concerning Haiti’s current political crisis offers the standard hand-wringing as they decry the “degradation of democratic institutions” and tentatively propose intervention by Western governments.

Even these predictable reactions are an improvement on the headlines of the recent past. American newspapers have been known to publish shockingly slanderous diatribes against Haitian culture and beliefs. As late as 2010, opinion sections were rife with blatant prejudice, expressed primarily through denunciations of Vodou, Haiti’s national religion.

Anthropologist Robert Lawless writes that “voodoo” is one of “few words in the English language that have the immediate power to produce images of revulsion.” In the 1980s, newspapers such as The Wall Street Journal made no secret of their disdain for Haitian “voodoo.” As one of their articles put it in 1988, “Western notions of progress and development fade in the smoke of a voodoo priest’s flaming magic stones.” The antipathy was so strong that the word “voodoo” began to be used as a pejorative in non-Haitian contexts, such as President H.W. Bush’s infamous phrase, “voodoo economics.” In 2000, a WSJ editorial called “Voodoo Journalism” reminded readers that "voodoo" is a code word meant to suggest that such an idea is hair-brained in the extreme—“too silly to merit discussion.”

When the 2010 earthquake annihilated Haitian lives and infrastructure, multiple establishment papers took the astonishingly insensitive approach of blaming the devastation on Haitian cultural deficiencies. David Brooks wrote for the New York Times that Haiti suffers from “a complex web of progress-resistant cultural influences,” citing “the influence of the voodoo religion, which spreads the message that life is capricious and planning futile.” The Wall Street Journal took the point even further. In “Haiti and the Voodoo Curse: The cultural roots of the country's endless misery,” Lawrence Harrison opined that Haiti “defied all development prescriptions” because its “culture is powerfully influenced by its religion, voodoo,” which he says is “without ethical content.”

Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, who is a Vodou priest as well as a Western scholar, experienced the prejudices of American journalists personally. “Soon after the [earthquake] in January 2010,” he writes, “I was assailed night and day by reporters from the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and CNN wanting to know about ‘blood rituals’ and about ‘peculiar funerary rites’ in the ‘Western hemisphere’s poorest country.’” When Bellegarde-Smith declined to assist in reinforcing demeaning stereotypes about his people and his faith in the midst of a national catastrophe, the journalists became hostile. “I was facing a horde of hungry reporters who wanted raw Haitian meat,” he remembers.

Had they done their historical due diligence, these journalists might have thought twice before launching their assault on both journalism ethics and basic human decency. During colonial rule, French plantation owners made a habit of vilifying Vodou, and American condemnation of the religion has been de rigeur since Haiti’s invasion by the U.S. Marines in 1915. On the boat to occupied Haiti, Marines were taught that Vodou practitioners were master poisoners, and upon arrival they sent home lurid accounts of barbarous African rituals. According to historian Mary Renda, in the years following the American occupation “writers continued to denigrate Haiti’s African origins and to peddle damning lies about Haitian religion.”

The concerted effort by both the media and the American government to dismiss Vodou and dehumanize those who believe in it has always been about more than religious intolerance. The first scornful account of Vodou was written in the late 18th century by a wealthy slave owner who feared its power to upend the plantation hierarchy. Over a century later, the Marines used racist accounts of Vodou to support the hegemonic project of turn of the century U.S. colonialism. It is almost startling how clearly these attitudes are echoed in mainstream coverage of the country today.

Contemporary journalists may be completely ignorant about Vodou, but it’s true that Haitians are powerfully influenced by it, though not in the way those who grossly stereotype it believe. Rarely is the extent to which Vodou provides deep social and spiritual support for Haitian people reported. As Bellegarde-Smith writes, “If Vodou were to unravel, its demise would bring unforeseen disruptions to every area of Haitian life.” Vodou priests serve vulnerable communities in countless ways; Vodou facilitates mutual aid, political organizing, and universal health care. When Haitians lose faith in the legal system, Vodou communities find ways to administer justice and repair the social fabric.

Vodou is also a potent source of historical memory; as its robust oral tradition can attest, Haiti’s national religion and history are inextricably tied. In 1791 the first shot of the Haitian Revolution was fired through ritual, when enslaved people gathered in the now-legendary forest clearing of Bois Caïman to call for spiritual aid in their war against the plantation. As filmmaker Maya Deren writes, Vodou helped find expression for “the rage against the evil fate the African suffered, the brutality of his displacement and his enslavement.” If the outcome of the revolution is any indicator, the prayers of the enslaved at Bois Caïman were answered in abundance, and the pursuit of social justice remains engrained in modern Vodou practice.

Accusing Vodou of lacking ethics says more about the morality of the Wall Street Journal than it does about Vodou. If Haitian Vodou is an expression of the collective desire to banish all forms of systemic oppression, then what exactly are those who denounce it opposing? Currently, Vodou is one of the few bulwarks Haitians have against the predations of nonprofits, disaster capitalists, and the Clintons. Far from being a national problem, Vodou has been one of the only consistent sources of national solutions. How, then, can one read a stance against it as anything other than a stance against Haitian independence?

News coverage of Haiti may be shameful, but observing its limitations presents us with a crucial opportunity to reevaluate our lenses. Media attitudes towards Haiti have historically articulated an unambiguous position in the ongoing global power struggle that originally evolved on the plantation. Examining them forces us to confront our own allegiances in that struggle.

As Haitians suffer the consequences of President Moïse’s asssassination in the months ahead, we would do well to learn as much as we can about the history of a nation so frequently caught in the crosshairs of international capital. “History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous,” writes Michel-Rolph Trouillot. “The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.”

Holly Devon is a writer and editor based in New Orleans. Get to know her better: @Holly_devon7

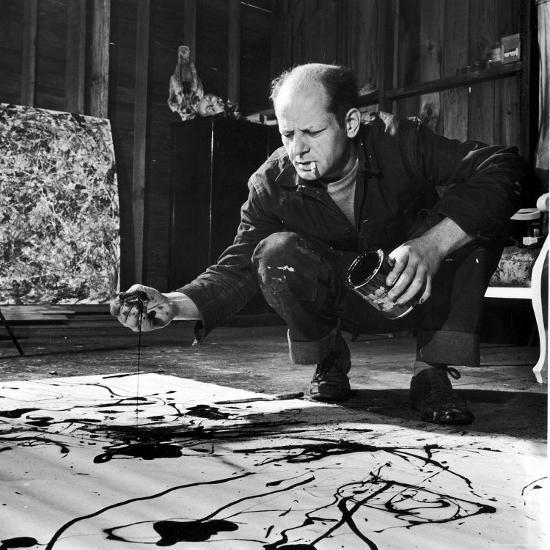

*Thumbnail image: Aerial Photograph of Port-au-Prince.