by Mikaela Dery

I find myself vaguely on edge whenever I approach a cluster of teenage girls on the street. This has always been the case—as everyone knows, teenage girls are a lethal combination of cool and terrifying—but the sensation has been particularly acute lately, and the other day I realized why. I was idling near the Prada store in SoHo (where I am wont to window shop and pretend I’m not panicked about my life), inspecting the outfits of one such group. One wore a cropped sweater vest and low-rise jeans, another a tight Fiorucci top and what looked like a Fendi Baguette under her arm. The third had a pink front-tie cardigan and perfectly glossed lips. It was, I thought, not just early-aughts fashion: their clothes were decidedly inspired by the mean girls of the era.

It’s no secret that the 2000s are back in style. Lyst, an online shopping platform that regularly publishes data, reported in February that searches for “Y2K and 2000s inspired fashion pieces” had increased by 80 percent since 2019. Fashion writers have posited that the surge in popularity of turn-of-the-millennium fashion is driven by the perception that the era was a simpler time, but even a cursory look at TikTok, Instagram, and the feeds of Depop sellers who traffic in 2000s nostalgia reveals that most people are drawing inspiration not just from the era generally, but from the female antagonists who dominated the decade in both fiction and the tabloids.

It was, after all, queen bee Regina George, not the homely Cady Heron, who wore the pleated skirts that are now skyrocketing in popularity; the Upper East Side’s Blair Waldorf who donned designer argyle sweaters—for which searches have increased by 45 percent—while she terrorized the students of Constance Billard; and it was mean girl tabloid fixture Paris Hilton who first popularized the Juicy Couture tracksuit. This week, Buzzfeed reported that teens are paying hundreds of dollars for the pink Gap Kids hoodie worn by a demonic Megan Fox in Jennifer’s Body.

Given the popularity of early-aughts style, it was not surprising to see elements of it reflected in Olivia Rodrigo’s “good 4 u” video (which, I am not ashamed to say, I watched within hours of its release). Directed by Petra Collins—herself a teen-dream connoisseur who got her start at Tavi Gevinson’s Rookie Mag—the video opens with Rodrigo seated in a sparse room being recorded by a number of Galaxy Z Flip smartphones: a new release from Samsung that mirrors the design of the beloved Motorola Razr, an essential for any mean girl in the 2000s. Many online commentators were quick to point out that the video echoes the 1999 Japanese horror film Audition, in which the main character’s supposed affection for men turns violent and murderous. But Rodrigo’s white cable-knit sweater, worn over a button-up shirt and paired with a plaid skirt and knee-high socks, would have been equally at home on the set of Gossip Girl.

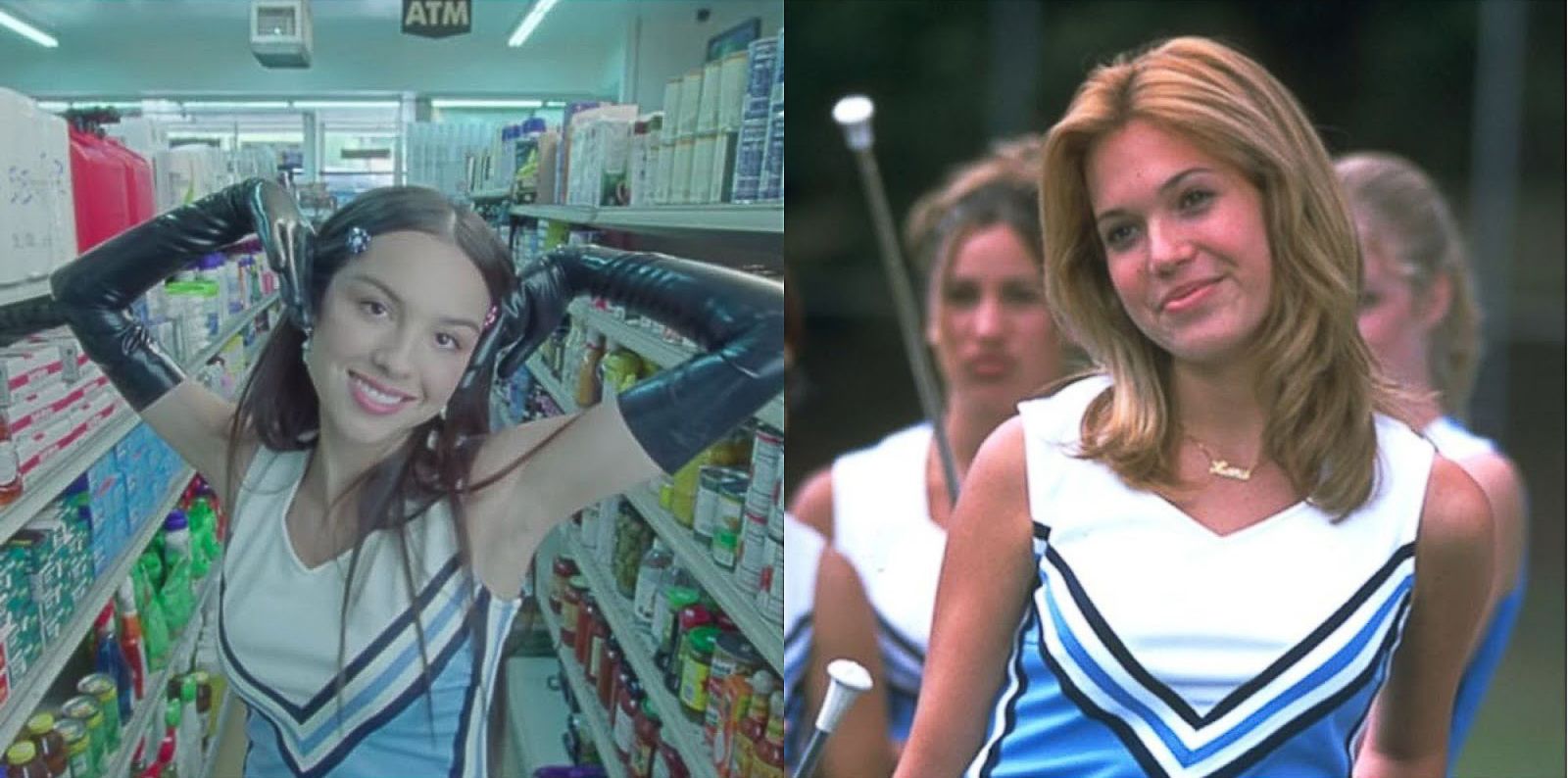

Next, we see her in a blue cheerleader uniform identical to the one Mandy Moore wears as mean girl Lana Thomas in The Princess Diaries (2001) while she terrorizes an angelic Anne Hathaway. Rodrigo eventually accessorizes the uniform with menacing black latex gloves, which she leaves on as she sets fire to her ex’s bedroom—while wearing yet another plaid, pleated skirt. She adds a cream bustier recently popularized by Tik Tok girls and Instagram influencers but that Prada first showed on its fall/winter 1999 collection. Of course, the video also contains multiple references to Jennifer’s Body, in which Megan Fox’s magnetic mean girl becomes a succubus after being brutally murdered by a Satanic touring punk band and kills high school boys to maintain her perfect appearance.

But the more I thought about the video, the less nostalgic it felt. 2000’s mean girls almost always embodied the phenomenon of relational aggression, a term often attributed to the psychologist Nicki R. Crick. Crick conducted extensive research on peer victimization in the mid ‘90s and concluded that, while boys were more likely to engage in physical aggression, girls were more likely to manipulate the people around them. This theory formed the foundation of the 2002 self-help book Queen Bees and Wannabes by Rosalind Wiseman. Tina Fey then adapted the book into Mean Girls (2004), where Regina George embodied relational aggression, as did many of her fictional contemporaries. Whether they directed their aggression at boys or girls, their actions were usually subliminal and deft, their rage coated in gentle femininity.

What is distinct about “good 4 u” is that it shows explicit, rather than implicit, aggression. As the video progresses, Rodrigo performs a riot grrl-infused cheerleading routine, purposely shoves another girl in the locker room, and tears items off shelves in the convenience store where she purchases the gasoline she later uses to exact pyromaniacal revenge on her ex. All the while, she sing-screams that he is a “damn sociopath” and fumes that he never seemed to care about her at all.

Female rage is, to some degree, endemic to the painful, complicated experience of being a teenage girl. This ordeal is neatly explained in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (2000), in which the Lisbon girls’ beautiful and illusive exteriors conceal their troubled interior lives. Memorably, the film opens with the youngest sister, Cecelia, talking to a therapist after her first suicide attempt. He tells her she’s “not even old enough to understand how bad life gets.” She responds: “Obviously, Doctor, you’ve never been a thirteen-year-old girl.”

That anger is even more justified at present. At a time when they should be discovering their independence, teenage girls are instead stuck at home, taking on more domestic responsibilities than their male peers and suffering from mental illness at higher rates. The latter is, in part, because of social media platforms which connected many young girls to the outside world during lockdown, but also feel tailor-made to prey on their insecurities. It’s all too unfair and too horrible.

Mean Girls alludes to a pre-pandemic version of this anger. At the end of the movie, Regina George storms down the lacrosse field while Cady narrates, “Her physical therapist taught her to channel all her rage into sports.” It is on full display in Jennifer’s Body, which never resolves the murderous fury that fuels Fox’s character. (At the time, Fox told Lynn Hirschberg that the film was “obviously a girl-power movie, but it’s also about how scary girls are. Girls can be a nightmare.”) That Collins and Rodrigo chose to fuse the image of the cool, calculating cheerleader with a murderous Megan Fox, suggests that—for them at least—the popularity of early-aughts mean girls surpasses nostalgia for a simpler time. Their hybrid aesthetic recasts these enduringly popular tropes to highlight the anger so many young girls feel.

It’s a sentiment that Rodrigo echoes on “Brutal,” the album’s opener, in which she sings, “I’m so insecure I think / That I’ll die before I drink.” And later, “I’m so sick of seventeen / Where’s my fucking teenage dream?”

Mikaela Dery edits Laid Off NYC's Fashion section. She holds an M.A. in Cultural Reporting and Criticism from NYU and has written for Bedford + Bowery, Guernica and others. She lives in Manhattan. Get to know her better: @mikidery

*Thumbnail image: Olivia Rodrigo in her “good 4 u” music video, directed by Petra Collins