by Sarah Pavlovna Goldberg

The Kremlin curates Vladimir Putin’s strongman image to show an air of impenetrability: shirtless and sunkissed on a horse, skiing in Sochi, hunting tigers, piercing a gray whale with a bow and arrow, slamming his Judo sparring partners to the floor. These images represent Russia’s centralized power structure, in which Putin (with the help of Kremlin photographers and his communications teams) needs to display that he is the only person strong, decisive, and manly enough to make executive decisions. While the Kremlin wages war on independent media avenues, Putin demands full control of his own political narrative.

On April 21, in his annual address, Putin threatened an “asymmetric, fast, and tough” retaliation against the West while strategically deploying 120,000 troops at the border to eastern Ukraine. The night prior, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (who campaigned on the promise to end this conflict) addressed Putin in a video: “Mr. Putin, I am ready to go even farther and invite you to meet anywhere in the Ukranian Donbas, where there is a war.” Russia pulled back their troops, and the Defense Ministry claimed the move was a training exercise—a symbolic response to the threat posed by President Zelensky’s path to NATO membership.

After President Biden imposed sanctions on Russia for the SolarWinds hack and called Putin a “killer” for his treatment of the imprisoned Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny, Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov—and the figurehead of the Ministry’s TikTok—sent home 10 U.S. diplomats. U.S. Ambassador to Russia John Sullivan was among those who returned to Washington indefinitely.

On April 26, obtaining a questionable order from the Moscow city courts, Russian authorities disbanded Navalny’s network of regional organizers, labeling them “extremist.” The Kremlin’s current reactionary maneuvers are informed by Putin’s first PR crisis as President.

It was August 2000, barely three months after Putin’s inauguration, and Russia was performing the largest naval exercise of the post-Soviet era, codename “Summer-X.” The goal was to show the world that after the embarrassment and economic trauma following the collapse of the U.S.S.R., Russia was not to be played with anymore.

Putin wanted to show himself to be the strongman that Boris Yeltsin, the first president of the Russian Federation, wasn’t. Thus, on August 12, 118 sailors aboard the nuclear submarine Kursk at the port of Vidyayevo were given a set of orders for the exercise, which was to take place in the Barents Sea. They were to arrive at a launch site, fire a torpedo, and return to shore.

On the second day of their exercises, as they left port, a faulty torpedo casing that was not welded properly began to leak high-test peroxide, a chemical that operates as a propellant. According to the official account provided by the Russian Navy’s report, “highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide used as torpedo fuel leaked into a torpedo compartment. That sparked a chain reaction with the copper and brass in the compartment,” causing an explosion of 1.5–2.2 magnitude on the Richter scale. The hull—specially built to withstand sinking—was breached as a result. As the Kursk hit the ocean floor, another 3.5–4.4 magnitude explosion occurred.

95 sailors were killed by the explosion. 23, miraculously, survived the blasts, having been in a different compartment of the submarine. There was a days-long window of opportunity to rescue the surviving sailors. The U.S., the British Government, Norway, France, Italy, and Israel offered rescue assistance. But the new Putin administration rejected foreign help. They felt that, because it was a Russian submarine, the rescue had to be a Russian job. It was to be a demonstration of might after the embarrassing Yeltsin years.

But Russia moved devastatingly slowly. At the time, Putin was vacationing in Sochi, a city on the Black Sea known as a summer destination. He first addressed the nation three days after the crisis occurred, still on the wrong sea, wearing his summer casuals, well-rested and tanned. In his speech, he floated the baseless idea that it was the American ship overseeing the exercise, the U.S.S. Memphis, that had collided with the Kursk. By the time he returned to Moscow, the Kursk had spent seven days on the seafloor. On the eighth day, Russia finally accepted assistance from the British Navy along with Norweigian divers. The few surviving sailors trapped aboard, waiting for outside assistance, were left to die. The tragedy was the result of systemic problems with the Russian navy—poor maintenance, budget cuts, lack of oversight and improper training—but it was ultimately blamed on Putin, its overseer.

I spoke to Jill Dougherty, Moscow Bureau Chief of CNN from 1997–2005, who covered the Kursk submarine disaster as it happened. “I remember when they finally said that the men had died,” she told me. “It wasn't a rescue anymore. It was a salvaging job. They could have been saved by outside help, but Russia wouldn't allow it—the government wouldn't allow it. They didn't want outsiders, especially the NATO countries … getting any secrets.”

The failures of the post-Soviet era had taken a profound toll already, Dougherty told me, and frustration was escalating. “There was fury, fury by people who were there, who lost families,” she said. “The whole nation was exhausted.”

Prior to the salvaging, the sailors’ families gathered in a Vidyayevo auditorium on August 18th for an official account from the military. It was a slew of empty words. Navy personnel rejected questions and criticism, and when asked for details, they said that such information was classified. “25 years with the Navy and for what?” a woman yelled, sobbing. A huddle of men obscured her from the press while a woman in a trenchcoat sedated her. When Putin came to Vidyayevo himself, he was confronted by an angry crowd. He later was quoted as calling the women whores for their outbursts.

A month later, Putin appeared on Larry King Live. His performance was infamously sociopathic: When King asked Putin about the submarine disaster, Putin said plainly, “It sank.” The corners of his mouth lifted into a discomforting smile.

Dougherty witnessed the Kremlin try hard to save face. “Right after that interview was shot, the Kremlin called the Bureau and said, you cannot air that interview,” she said. “I said, ‘We can't stop it. That is the Larry King show. They make their own decisions and we can't not broadcast an interview.’”

In 1999, months prior to Putin taking office, Yeltsin’s Kremlin bombed apartment buildings in Moscow and other cities, blaming Chechen rebels, in a gruesome attempt to cast Putin as his strongman successor and justify a second war with Chechnya.

“The apartment bombings appeared to be a keystone of the plot to confuse Russian public opinion, to create terror, to distract the Russian public to redirect their attention away from the corruption,” said Financial Times Russia correspondent David Satter. Satter’s 2014 expulsion from the country for his reporting, which pointed to the Federal Security Service (FSB) as the orchestrators of the bombings, can be interpreted as an admission of guilt. From then on, Putin’s administration was determined to locate and justify itself within the office it inherited. If the administration was the instigator, the administration was the solution.

The Kremlin went to war with dissidents. The late Anna Politkovskaya survived many years of Kremlin persecution for her investigative work covering the Kremlin’s role in Chechnya. She was threatened, followed, poisoned, and jailed over the course of six years before being murdered in the elevator of her apartment building in 2006. In the recent past we’ve seen the defenestrations of doctors and journalists, and the poisonings and attempted murders of Alexei Navalny, Vladimir Kara-Murza, and Alexander Litveninko, among other Kremlin critics. In the most recent scandal, Putin has cast himself as the victim of the CIA, claiming that Navalny and the independent media are foreign agents.

Putin’s oppositionists and critics have gained political traction of late, and he is willing to go to great lengths to have them handled. While Navalny awaited sentencing upon returning from Germany, his supporters held protests in over 100 Russian cities. Upon his sentencing, approximately 100,000 showed up to protest the Kremlin.

Navalny’s movement posed a deep threat to the Kremlin’s ability to control the narrative. And in its reactivity, the Kremlin’s dispatches are increasingly out of touch, and no longer as tactical as they were in the aughts and ‘10s, the simple days.

During the protests, TikTok, among other social media platforms such as Instagram and Telegram, became valuable organizing tools that mobilized thousands of people. Anti-Putin TikTok trends emerged. Many students removed the president’s photo from their classrooms; some shared information about how to stay safe at the protests.

The Russian Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Emergency Situations joined TikTok one day apart from each other in early February and subsequently limited the app in Russia. Their videos are a festival of insecurity and reactivity.

In their very first TikTok, the Foreign Ministry rips a Navalny video criticizing Russia’s Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine. An intro reads “Don’t let yourself be fooled ;).” The video cuts to Navalny, who says, “Putin’s lie about the Russian scientists having invented, registered, and tested the vaccine and are able to administer the vaccine is so obvious that it has caused nothing but laughter.” Then, it cuts to footage of EU minister Josep Borrell saying he had high hopes for Sputnik V. The caption: “No Comment.”

@midrussia Без комментариев

♬ original sound - МИД России

The Foreign Ministry videos showcase their catalog of septuagenarian male diplomats and ambassadors and their man at the helm, Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov. In one clip, ambassador to Spain Yuri Korchagin poses for photos to the tune of the intro to Back In Black by AC/DC. In another, we see ambassadors floridly wishing their dearest women a happy International Women’s Day. The play-to-like ratio of these videos are miserable in comparison to other popular content in the TikTok space. A video of an Emergency Situations employee balancing on an axe has not done very well for their play-to-like ratio, either.

TikTok, like most apps, collects user data to track behaviors and interests in order to direct users to content within their perceived interests. A user’s TikTok behaviors—interaction with hashtags, shares, number of times they might have viewed one video—determine what appears on their tailored “For You” page. The Kremlin’s lack of knowledge in the TikTok space exhibits that if social media metrics are truly of interest to them, they’re not quite sure how to play them.

It’s clear that the administration’s strategic deployment of TikToks is multi-functional: distraction, flooding the zone, and addressing Navalny’s claims. With mass unrest and dissatisfaction, as independent media outlets are labeled foreign agents, we are invited to this lampoon of a government official riding a scooter to The Doors’ “Riders on the Storm.” Had the Kursk tragedy happened in 2021, would there be another bleak TikTok about it, blaming the CIA?

The Foreign Ministry’s TikToks shield the dark truth behind the Interior Ministry, the FSB, and the military, Putin’s defenders. Russia’s Interior Ministry—which oversees the police, security, and law enforcement—is plagued by competition for influence and overlapping responsibilities while fighting the war against dissent. “They compete for budgets, they compete for turf and they compete for illegal streams of money,” Brian Taylor, Professor of Political Studies at Syracuse, told me. “The ability to instigate criminal cases, for example, can be monetized to take one side or another in a business dispute,” Taylor said.

With a backdrop of corruption, the Interior Ministry is a brutal entity in the war for narrative control. Police visit the homes of Team Navalny coordinators and allies on a daily basis and raid Navalny’s offices across the country. In a video announcement following a breach of the Team Navalny database that exposed the email addresses of 440,000 registered protesters, Leonid Volkov and Ivan Zhdanov, the leaders of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) rallied their supporters via Youtube to attend the April 21st protests. “Have you ever seen with your own eyes how a person is killed? You have. You see it right now,” they said. Volkov and Zhdanov implored Navalny’s supporters not to grow complacent: “No matter how much you want to abstract, to not think about it, to change the subject, this will not change the fact that Alexei Navalny is being killed. In a scary way. In front of all of us.” On April 29th, they announced that they were disbanding the Navalny offices due to these raids, and that they would be organizing from home.

On the day of the protests, live feeds disseminated scenes from city to city. Nearly 2,000 people were detained on the day of the protest (data updated in real time and by location on this map). TV Rain, an independent news outlet, published a video to their Telegram page showing a bus full of protesters arrested by police. Clips on their Twitter feed show vicious police brutality.

Putin fiercely deploys the tools available to him to sustain his rule through entrenched authoritarianism. The Putin meme created by his administration casts him as effortlessly in control of nature, godly in his stature, the master of everything he tries, crushing internal and external enemies. His desire for control is reminiscent of the airbrushing of the Stalin era, wherein the party apparatchiks who fell out of favor were erased from the era’s photographs in an attempt to rewrite history. But today, when truth often depends on algorithms, centralized communication can’t exist—and it’s clear from their dated PR that the administration laments it.

Sarah Pavlovna Goldberg thinks a lot about Russian politics. Get to know her better: @solidgoldsarah

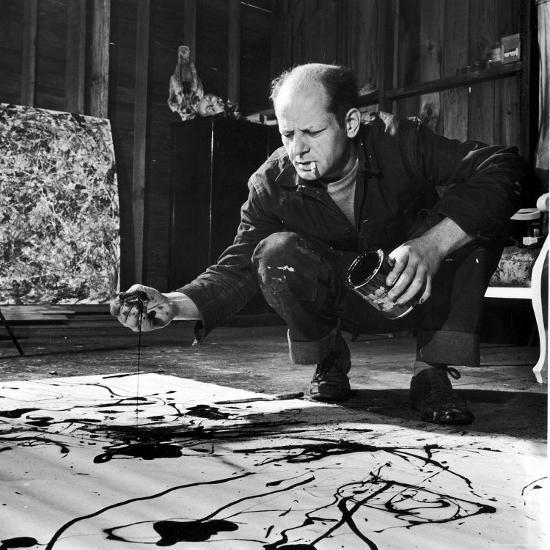

*Thumbnail image by Alexei Druzhinin (AP) from Kremlin pool.