Written by Joseph Mooney & photos by Emmet Padgett.

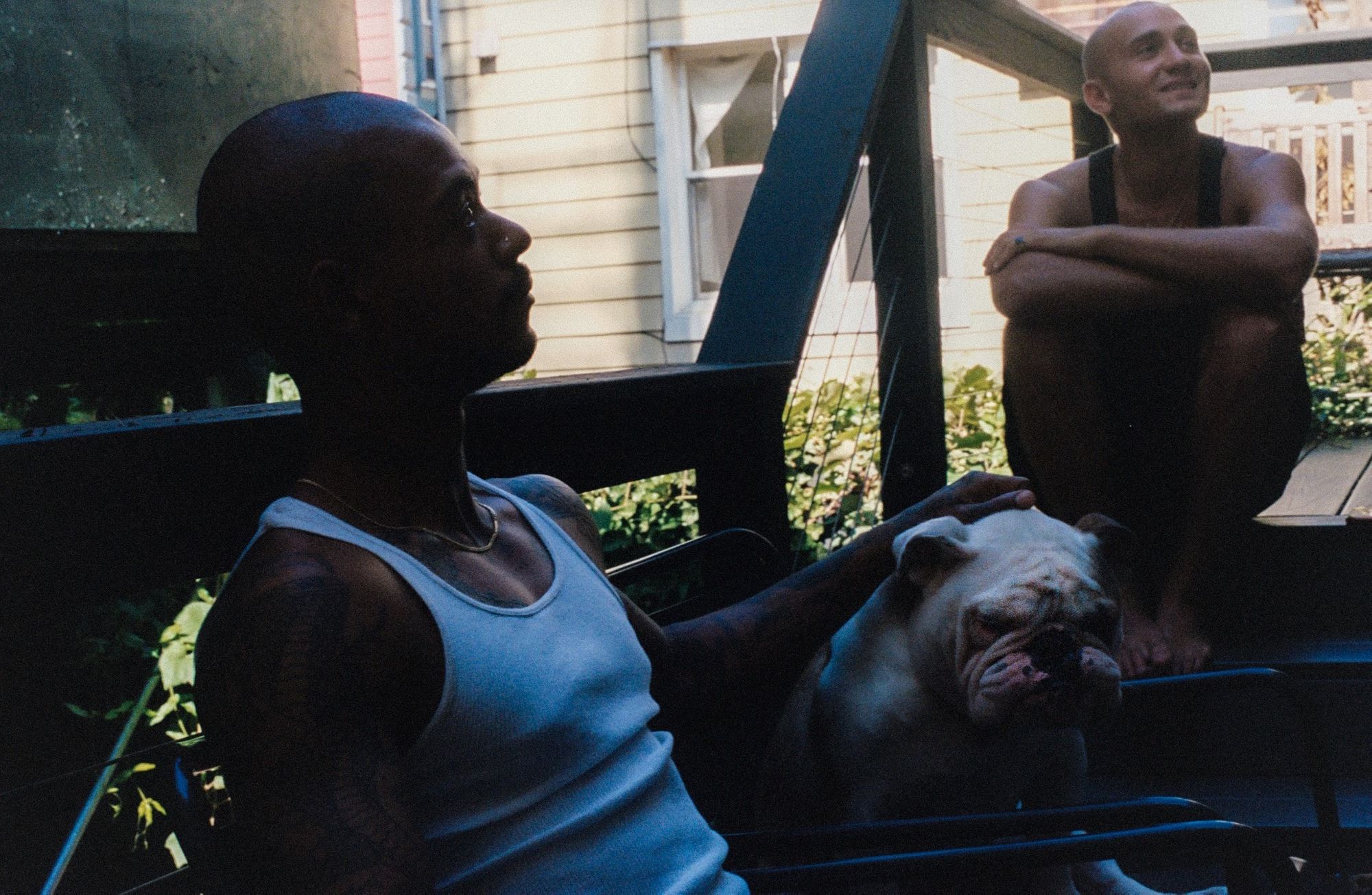

Arriving to interview Jesse Gibson I am greeted by Papi, a cozy English Bulldog, and by Jesse, clad in black boxing shorts. No shirt is needed; his tattoos create a mosaic on his torso. We sit in an open-plan kitchen-cum-lounge with handcrafted wooden surfaces, and surfboards lining the exterior.

I first met Jesse years ago, at the height of our teenage rebellion. I think we were 16. Since then we’ve had little communication. Jesse is quiet at first—there’s a certain mystique to him. Papi needs his ears scratched. Emmet and Antonio lounge on the diagonal sofas next to us.As we slowly settle in for the interview, Jesse’s reserve lifts. He’s a natural wit, logical and self-reflecting. His debut album Before the Devil Knows We’re Dead is just about to be released.

We start with talking about his nomadic childhood.

JM: You’ve moved around a lot in your life, haven’t you mate?

JG: Yeah, definitely. I was born in Kenya, moved to New York when I was about 6 months old. I lived in Queens for a bit, till I was maybe 10. And then I moved to West Africa, to Benin, with my dad. We were out there for about a year before coming back to the States, and then I was in Nebraska for about 6 months.

JM: So you went from Africa to Nebraska, and NYC in between.

JG: Yeah, it was a racist little shitty town in Nebraska. But, it was cool for a second until I really got the gist of it. I had a lot of crazy experiences there. And after that we moved to Kampala, Uganda for about 4 years.

JM: I hear Kampala is a pretty vibrant place. I have a vision of dirt roads and motorcycles. Am I onto something?

JG: Nah, I was driving cars. A couple of my homies were doing motor-cross, but I was never good at that. I crashed all the time. I also crashed a lot of cars—I probably wasn’t great at that either. Uganda’s pretty crazy. Everyone was going to the club at a young age and nobody blinked an eye. Back then it felt so regular, but I literally was a fucking baby walking into a club like, “Lemme get a redbull vodka.” And everybody was super casual about it; nobody gave a fuck. It was crazy. I got expelled from every international school out there.

JM: For what?

JG: Fighting, selling weed, being stupid. Then I got enrolled into this Christian international school. The only reason they let me in is because they actually thought I was possessed. I had to stay after school every day for like a month while the bible teacher did some weird exorcism shit on me. It was fucked up because she was hot and young. I asked her, “Are you ever gonna have a boyfriend?” and she was like “No, not till I’m married.” She was on some shit; she never even hugged her dad. That was trippy. I got expelled from there because I hooked up with the pastor’s daughter. After that my dad said, “Well, there’s nowhere else for you to go.” So we had to come back to New York, and that’s when I moved to Williamsburg, South 5th and Driggs. Actually I was on Meserole for a second, and that’s where I met all the homies.

JM: What did your dad do that meant you moved around so much?

JG: He worked for non-profit organizations: PLAN and then Save the Children.

JM: Is he originally from New York?

JG: No, he’s from Hastings, Nebraska. That’s where his family’s at. Now he’s retired in Guatemala. Shoutout my dad!

JM: When did music start to become a big thing in your life?

JG: Music has always been fundamental in my life. My dad plays guitar. He always wanted to be a musician. I grew up listening to classic rock and playing guitar with him.

JM: Did you join the Christian rock choir at your school?

JG: Never. No, never. But there is one funny story. Every Friday they had this morning meeting with the whole school, and somebody always had to read a bible verse, and I came in mad high and hella late and the principal was like, “Jesse, read chapters whatever-the-fuck.” So I’m going through the bible and remember that a couple of days before I had smoked a couple of pages from it, used it as roll-up. And I’m standing mad smacked on stage in front of the whole school like, ”My bible don’t have that.” And my teacher was like, “It’s the bible! What do you mean it doesn’t have that?” So she came up to the stage and saw the pages were obviously ripped out. I got in a lot of trouble for that.

JM: Do you think this sort of sacrilegious shit comes out in your music?

JG: I mean it’s probably why it’s a little on the emo side.

JM: Did you start listening to more of that type of music in Christian school?

JG: When I was in Uganda I was listening to a lot of hardcore punk. And I had this Japanese homie, Kayo, who was nasty at the guitar and listened to a lot of screamo music. I was rocking skinny ass jeans and doing that whole vibe for a second. I was playing a little guitar and singing. I was moshing, dude. That was my first try at the rock stuff. It didn’t go anywhere; we played one talent show. It was sick but we weren’t the best.

Then I started skating and the rock shit phased out for a while, because I was really only listening to hip-hop and trap music. It started with Wiz Khalifa. I was smoking a lot of weed and making mad rap songs over his beats. That was my first attempt at trying to drop a mixtape. It was trash, but I just kept doing it. I started rapping with this kid Nelson Dardon, Louis D, who really put me on this New York rap shit. And then through that, I met Capital Steez, RIP. We were going to the Union Square Cyphers, and that was what made me be like, “Alright, yo, this rap shit is where it’s at.”

JM: So when were you like, “I’m gonna start putting a lot more effort into expressing myself through music?”

JG: I’ve always wanted to make music since I was a kid. That’s always been my dream, other than trying to be a professional skateboarder, but I saw that wasn't gonna happen at a very early age. [Laughs] So I was rapping, trying different shit, mixing up flows, doing all sorts of weird stuff, and I shot a music video with my homie Emmett. We were all super fucked up, so it didn’t really go as planned, or maybe it did… I don’t even know what we were planning. It was over a Frank Ocean beat. I was doing more R&B stuff, and then I was trying to be on some trap kind of wave, and I started recording at my homie Juju Merk’s studio in the Lower East Side. One day, homie put on this beat and I started to freestyle over that kinda thing. I literally wrote the lyrics within 5 minutes. My homies went on a deli run, and when they came back, the track was recorded. And that ended up being “Lowlife.” From then on it just felt like the right way to go.

I feel super blessed to be able to work with my homies. That's all I’ve ever wanted to do, to have everyone keep elevating their shit, leveling up. And that’s definitely where I feel we’re at. It’s been a long time coming. This shit didn’t happen that early. Drugs probably had a lot to do with that. Partying in the city, definitely gets crazy, you know.

JM: But it also gets you to know everyone in the city.

JG: Yeah, but it’s such a sink or swim sort of city. You can get stuck in that shit and really be lost, or you can find a way out. And like, luckily, me and a good amount of homies got out.

JM: It’s almost like a creative outlet, isn’t it?

JG: Yeah, I definitely wouldn’t be making the music I’m making without those experiences And I'm grateful to have the homies backing everything and being a part of it. I got my homie Max managing me! That’s a blessing.

JM: There’s a certain vibe you get with “Lowlife,” storming down a rainy street thinking about your ex-girlfriend.And “Lost in Translation” explores the dynamics of a relationship, combining “Oh shit, I love this person; this person means everything to me,” with “We don’t know how to talk to each other. We don’t know how to express ourselves. We don’t understand each other’s love language.” Do you think your communication with women has changed in the process of making this album? And do you reflect positively on your exes, given how they seem to have influenced your music?

JG: I had just gotten out of a crazy relationship when everything started happening with this album, and that definitely went into it. I do feel I have a different approach now. My last relationship was my first serious one. We were together for close to 4 years.

JM: How’d it end?

JG: It ended. I got love for her for sure, but it all happened super fast. We moved in together, got a dog (Papi!). And it was awesome, but it’s a lot, doing that shit so young. It got real serious real quick, and a lot is put into that emotionally. I definitely felt like I was being held back from a lot of music stuff. But all that resulted in this. So I feel like it was all a blessing in disguise. That whole relationship and [all my] prior experiences resulted in Before the Devil Knows We’re Dead.

JM: "So Sick” gave me that sunken stomach feeling, when you and your girl break up and it’s like, “Fuck, this girl won’t get out of my head.” You feel done with her, but you’re still thinking about her and those nightmares slowly start becoming a reality.

JG: Yeah, that's definitely the vibe, being so heartbroken. I’ve definitely had spells when I go on a bender, not sleeping, not eating. By the end of it you feel like you’re dead.

JM: Your music is a really nice marriage of alternative rock and emo rap. I couldn’t really put it into a category.

JG: I’m on an indie playlist, so if anyone asks, I’m indie. I’ve been skating since I was 12 and surfing since I was 18. That definitely has affected my music too. I listened to a lot of Sublime and Blink 182 and fucking Sum 41 and whatever-the-fuck, Panic at the Disco! and shit. I listen to a fuckload of Fall Out Boy. My music is reminiscent of that early 2000s, late 90s era. I feel like that’s a vibe that kind of got lost, and I’m just trying to do something different.

JM: “The Ride” is crazy. Can you talk about how you made that and who you made it with?

JG: “The Ride” was produced by Juju Murk and mastered by Matt Cohen. That’s one of my favorite tracks for sure. I remember when he first played that track for me. I was like, “Woah,we gotta go in on this.”

JM: What’s the process like when you get to the studio? Do you have to listen to a song over and over again? And are they normally written before you walk in?

JG: I usually have the beat prior, and I’ll just smoke a little weed and write up some stuff. The process is just going in there and having fun, honestly. Juju has helped me so much through all of this. I was a little unsure of the whole thing, and having Juju there to be like, “Yo, this is it,” helped me be more confident about everything.

JM: Did you work with Juju on the whole album?

JG: Uh, yeah. Pretty much all of the beats are his, and the ones that aren’t, I recorded at his studio.

JM: Is there a specific emotion you want to evoke in people when listening to you?

JG: All is fair and nothing more. At the end of the day, whatever's going to happen in your relationship is going to happen. My parents divorced before I was even born. I don’t know if I even realized that shit. I didn’t think it affected me until later down the line. But more than half of New York is probably growing up in broken families. It’s just a part of society. Nobody’s perfect and you can only learn from your mistakes. Life’s purpose is falling in love and having those experiences. It does take an emotional toll, and not everything's perfect, not everything is going to last. But I’m always going to cherish those experiences.

JM: How did you think this pandemic and everything with BLM has changed the way you relate to music? Has not being able to perform live affected you a lot?

JG: I'm cruising right now, in terms of the music. Not performing is frustrating, but I'm just hype to have something out that everyone can listen to. In terms of BLM, I have dealt with a handful of racism in my life. I’m all about the movement. It does feel kind of weird to be making the music I make. I just hope I can reach out to enough Black people that fuck with the vibe. There’s not many Black surfers out. Shout out all the Black surfers out there and the Black Surfing Association. I just want to put people on to something different. There are so many Black kids that listen to rock and are in that scene. I’m hoping I can have a super diverse group of people that listen to me.

I’m mixed. My dad’s white and my mom is from Mozambique. I grew up super open to everything and was also super aware of how racist America could be. I saw that through the way my father had to deal with everything. He had to deal with a lot of shit for marrying a Black woman.

The homies and I have been out there protesting. Hopefully we don’t have Trump as president again, and we can actually have some change. Fuck the police.

Before the Devil Knows We’re Dead is now out on Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal & check Jesse out on the gram @hessefuego.

Check LONYC weekly our take on: music, film, food, fashion, politics, photography and creative writing. Follow us, feel the vibe @laidoffny.

Follow Emmet's Instagram, for all his latest photographic conceptions @inspector.padgett