Words and Photos by Dan Girma

In March, 2018, a month before Abiy Ahmed was appointed prime minister of Ethiopia, I was in Aksum, the historical center of the Tigray region. I was there with a team of field geologists on invitation by the Ethiopian government to survey the country’s growing gem industry. As an Ethiopian American, my team hoped that I could serve as a cultural middleman.

We stayed at the Sabean International Hotel, one of the many buildings that have sprouted on the city’s main road in the past twenty years of high-speed development. It was the 122nd anniversary of the Battle of Adwa, Ethiopia’s decisive victory against the Italians and the day the country first defended her statehood. Adwa is less than an hour away from Aksum. The television behind the hotel’s lobby bar played a reenactment of Ethiopian soldiers marching to battle.

Beside me, old men in full military dress, tricolor sashes across their torsos, enjoyed a round of sodas while they waited for a car to take them to the memorial service in Adwa. Medal ribbons swayed under their chins as they lurched forward to grab their bottles from the table. They seemed old enough to be World War II veterans.

The Tigray region has long been the arena where Ethiopia has affirmed her sovereignty. Ras Mengesha Yohannes, governor of Tigray and one of Emperor Menelik II’s most important generals at Adwa, staged bitter rebellions following the victory. Tigray was where some of the last Italian garrisons were flushed out during World War II. The first rebellions after Haile Selassie reassumed power in 1941 occurred there. And in the 17-year civil war that pitted the communist Derg against an entire spectrum of ethnic paramilitary groups, it was the Tigray People's Liberation Front that stood above the others. With Meles Zenawi, the man who became Ethiopia’s first and longest-serving prime minister, the TPLF were the principal architects of a new Ethiopia, one that, for the first time, addressed the diversity and autonomy of the more than 80 ethnic groups that make up the country under a policy of ethnic federalism.

Once again, it appears that all roads lead to Tigray. The TPLF, no longer in power, launched a surprise attack against the Ethiopian National Defense Force’s Northern Command on November 4th. Abiy immediately ordered a state emergency and military intervention in the region. Since that declaration Northern Ethiopia has been plunged into obscurity, misinformation, and propaganda. Each side accuses the other of war crimes. There are rumors that Eritrea has joined the fighting on the side of the government. At this moment the Ethiopian National Defense Force could control anywhere between a quarter and half of the region.

What we do know is that ethnic cleansing has begun between Amhara and Tigray; tens of thousands of refugees have fled the region into Sudan. Government forces have taken Mekele, the regional capital and home to half a million, after Abiy’s ultimatum to surrender or face a full-scale bombardment expired. Tigray’s regional president still refuses to submit. A protracted war between the Ethiopian government and outstanding Tigray rebels continues to this day.

It’s hard to discern how much of this the prime minister expected when he assumed office in 2018. A reformer and long time political infighter, Abiy was appointed to quell the rising tide of cultural unrest that followed Meles’ death. Ethnic federalism was failing. The Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front, a multi-ethnic coalition founded during the civil war, was overtly controlled by the TPLF. Tigrayans held the levers of power in parliament, the military, and the church. Political and ethnic dissent was quashed; imprisonments and exiles were the norm. In the months preceding Abiy's appointment, members of the Oromo, the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia and the one to which he belongs, were protesting against political oppression. The roads to Addis Ababa were choked by the demonstrations.

I had explained to my team that I would be of little help in Tigray. None of the miners would speak Amharic, the language my family speaks at home and what foreigners default to when they think of an Ethiopian tongue. As part of a federalist initiative in 1994, Amharic was replaced by the dozens of native tongues as the language of instruction in primary schools, while English became the language of secondary and higher education. In a country where roughly half of children complete their primary education, and where 60 percent of the population is under 25, this has resulted in immense cultural divides.

Abiy tackled the country’s division head on, espousing his unifying message of Medemer (coming together). Taking office with a wave of popular support behind him, the prime minister acted quickly. He granted blanket amnesty for even the most extreme dissenters, allowing separatists groups like the Oromo Liberation Front to operate openly for the first time in years. He advocated for more privatization of lands and industries, an about-face from the previous policies that had helped the TPLF maintain its wealth and power. Most critical to the current conflict, Abiy dissolved the EPRDF and remade it as a single Prosperity Party, beginning a shift towards more centralized power in what the party’s by-laws call a “true” federalism. The TPLF was the only major party that refused to join.

Such a political turn was never going to be easy. The TPLF was never going to recede from total control willingly. But what Abiy was not prepared for was the country-wide support for the party’s core philosophy (however little it was practiced during their regime): autonomy and self-determination. One year ago, a failed coup in the Amhara region killed both the regional its president and the country’s army chief. That same year, the Sidama, Ethiopia’s fifth largest ethnic group, held a referendum to secede from its own highly diverse state. The referendum was tainted by violence in the preceding months.

These events are only highlights of the sectarianism that has spilled blood across regions during Abiy’s time as prime minister, as diverse borderlands are redrawn through lethal force. The Gedeo were the first major casualty; 800,000 were forced to flee their native lands, eclipsing the exodus of the Rohingya in Myanmar. In Abiy’s first year alone, the number of violently displaced persons nearly tripled, from 1 to 2.9 million. And while the number has fallen since 2019, it is still the third largest refugee population in the world.

Meanwhile, Abiy attempts to rally the people against the TPLF. He labels them a rogue clique that stands for everything the Ethiopian people are against. But his stance refuses to acknowledge the domestic support for ethnic autonomy and self-determination. In an Afrobarometer poll from August 2020, 61 percent of Ethiopians believed that federalism was necessary due to the country’s ethnic diversity, with the vote evenly split between ethnic and geographic federalism.

To make matters worse, Abiy has reverted to political measures more akin to the TPLF’s. Unlike many of its peers who have held elections in 2020, Ethiopia has postponed elections twice in the past year due to the pandemic. The delay has given Abiy the opportunity to roll back some of his earlier liberalism. Jawar Mohammed, an Oromo nationalist who preached self-determination, was allowed to reenter the country in 2018. At first an Abiy supporter, Jawar has since denounced the prime minister and for a time was his main rival in an upcoming election. He was detained on terrorism charges in September. Eskinder Nega, the internationally acclaimed journalist who was imprisoned multiple times on terrorism and treason charges while Meles was in power, has once again been detained on accusations of inciting violence following the death of Oromo singer Hachalu Hundessa.

Such actions have some Ethiopians fearing that Abiy is moving towards the type of blatant unitary control that hasn’t existed since the Derg. This is partially an issue of optics. The federalism marshalled by the TPLF was a thin veneer that masked centralized Tigray control. But that is precisely why the public hoped for real representation when Abiy came to power. Instead, the prime minister’s unifying rhetoric has shifted from an internal focus to an external one. Egypt and Sudan’s concerns towards the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, an infrastructural dream that goes back to Haile Selassie, serves as a rallying point.

“If there is a need to go to war,” Abiy said at a parliamentary Q&A less than a month after winning the Nobel Peace Prize, “we could get millions readied.” Medemer has shifted from inclusive to protectionist. What began as a plea to come together has morphed into a call to defend from outside threats.

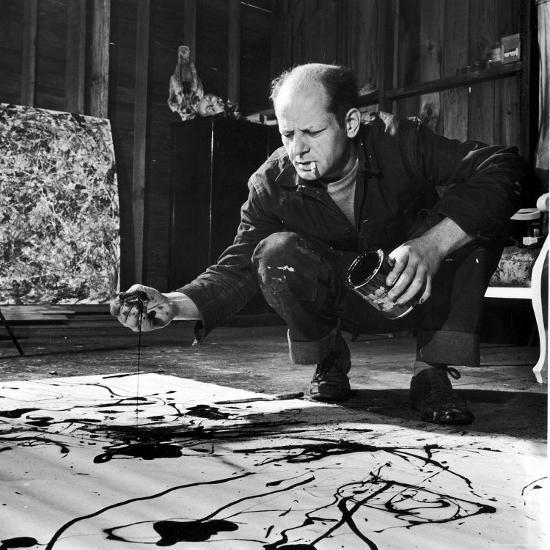

Our survey took us to Ch’ila, a village two hours north of Aksum. The area was in the throes of a sapphire boom, and Tigrayans walked miles each day to dig in the dry riverbeds where the gems were found. Like much of the country, the locals lived off of agriculture, and had applied their agrarian work ethic to mining. Entire families took part in excavating with shovels and mattocks, sifting through soil, and removing groundwater pail by pail. Children, accustomed to working in the fields, were given toy-sized tools.

I wanted to speak to them, but our guide, a regional civil servant from the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, would not translate for me. My team head told me that we could not include child labor in our report, lest the government revoke access to the area. Instead, we mingled wordlessly, spoke with smiles, and posed for pictures in the morning sunlight.

Daniel Girma is Laid Off NYC’s content curator and co-edits our Politics section. Get to know him better: @dangirmanyc