by Sara Krolewski

A few years ago, I had the fortune of being rejected from nine PhD programs in English. Nine. To this day, the number still feels like a rebuke, though the PhD-free years that followed have proved more rich, strange, and happy than I assumed they would be. “I think you just didn’t have enough experience for them,” my undergraduate advisor told me kindly as I sat in her office, choking back tears. She was right, of course—my thinking was shallow, my understanding of books mainly limited to facts I’d amassed for the multiple-choice GRE in Literature. (But I can list every kind of sonnet! I wanted to wail.) I hated them, the universities and their nebbish admission committees. They were so bored by their own middle-aged lives, I imagined, that they could only derive pleasure by inflicting pain on me, an innocent who merely loved to read and write.

Rest assured, I no longer think of myself in that way. (And “loving to read and write” is no reason to apply for a PhD.) But in the intervening years, I have come to consider my failure as a release from a career path that has become agonizingly competitive. Over the course of a decade, academic jobs in English have decreased by over 50% percent, and the numbers continue to fall each year. These are dismal times to want to be any kind of writer, but an academic? You’d be better off living like the Phantom of the Opera in a dusty library or bookstore—haunting the stacks, moaning to patrons about Henry James. At least someone would be forced to listen to you.

Christine Smallwood’s intoxicating debut novel, The Life of the Mind, explores the decline of academia with grace and fierce, unflappable clarity. (Smallwood is a critic and journalist, with a PhD in English literature; the short story on which this novel is based was first published in n+1.) We open in a bathroom stall of a library in a New York City university where Dorothy, a perpetual adjunct professor in English, is “taking a shit,” as the first line of the novel so memorably puts it. I am writing this in the library of a New York City university (where, happily, I am not getting a PhD); I have just returned to my desk from the cold, forbidding bathroom. Like Dorothy, I am often taken by the flyers posted on stall doors. The notice Dorothy spies from the toilet is for a mental health helpline, covered in obscene doodling. (She hopes that none of the artists are her students.) I tend to see signs related to women’s health or sexual assault, which always seem tepid and weirdly impersonal. “You are not alone!” they assure me, though I never quite feel comforted. Certainly, none of those flyers would tell you how to handle a miscarriage in a tiny bathroom stall, which is what Dorothy, in addition to shitting, is doing.

Make no mistake: this is not a sudden event, a loss that slices through the thin fabric of quotidian life. What troubles Dorothy most about the miscarriage—she is on “day six” of bleeding when the novel begins—is its ceaselessness. “The result,” to Dorothy, “was less than a trauma and more than an inconvenience.”

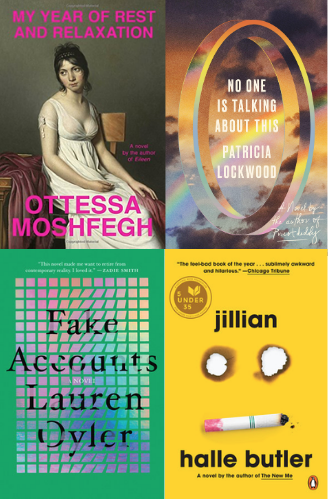

It’s easy to assume that Dorothy is an indifferent, even caustic protagonist, like the hard-bitten narrator of Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018) or Megan, the sullen millennial pitted against the titular character in Halle Butler’s Jillian (2015). But unlike those women—who seem to regard anything outside of themselves with heavy disdain—Dorothy is not detached or dismissive as much as she is distracted. Her thinking ripples from the bodily (the bloodied, “thick, curdled knots of string” clumped in the toilet) to the hypothetical: she envisions the children she might still have in the future as refugees from the climate crisis, “floating on rafts roped together with the fall coats everyone had thrown away because there was no more fall.” She half-heartedly attends therapy—though she cannot bring herself to admit her miscarriage to either of her therapists (she has two)—and hangs around with a friend, or maybe frenemy, who remains oblivious to Dorothy’s own difficulties. Dorothy’s boyfriend, though affable and endearing, is more of a sounding board than a partner; at times, his presence barely seems to register. And, though she should be reading constantly, Dorothy cannot concentrate on a book for more than a few minutes. If academics are expected to be unflagging martyrs to the feat of focus, Dorothy is not a very good academic. Her attention problems, it seems, are why she can’t escape from “adjunct hell.”

Or so we might think. What becomes abundantly clear throughout the novel is that Dorothy is more committed to literature, and to her duties as a professor, than the average disillusioned academic—even as she feels herself to be a failure. “You could do so much damage, giving someone a book at the wrong time,” she reflects. “You could prevent them from loving it, or—and this could be worse—make them love it too much, or too stupidly… Teaching was an enormous responsibility. Dorothy hated it.”

Academics tend to deprioritize teaching, which is seen as a strain on research time and a hindrance to critical development. Coaxing insight out of kids who don’t feel the same urgency about literature that you do can be draining, to say the least. Dorothy shares these concerns (though she isn’t getting much research done), but as an adjunct, she knows her only choice is to teach—to try, at least, to look cheerful and engaged as she faces down a classroom filled with “expressions of boredom, confusion, and the kind of rapid stuttery nodding that indicated artificial stimulation.” In these scenes, I felt a sharp pang of sympathy for Dorothy, and a fluttering of guilt from my own college days. Did I think of my professors as people, or as providers of grades and criticism, to be flattered and cajoled?

One of the small but intense pleasures of this novel is its portrayal of a truly idiosyncratic life: Dorothy is undeniably a person, even if her students don’t see her as one. She’s as addicted to her phone as anyone else—frittering time away on Instagram, checking her bank account app in panicked intervals—but she’s not the kind of irony-poisoned Twitter fanatic we are seeing more and more of in women-authored literature, namely Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This and Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts, both published in February. (Lockwood and Oyler, like Smallwood, are accomplished critics and first-time novelists.) Many reviewers of these (admittedly very interesting and dynamic) novels have implied that Lockwood and Oyler’s narrators are universal types: stand-ins for the white, upper-middle-class, overeducated millennial woman. She is assumed to be a perpetual Poster—or, in Lockwood’s case, Shit-Poster—darkly intelligent but deeply unhappy.

I’ve taken to calling this character the “E-Girl Adrift,” in homage to Katie Roiphe’s inspired term, the “Smart Woman Adrift,” which she ascribes to the anxious, self-sabotaging, yet strikingly clever women in the novels of Renata Adler, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Joan Didion. Dorothy is also a white, overeducated, older millennial, though, like a growing number of academics, she is more downwardly mobile than upper-middle-class. But the life she leads feels richer, and more realistically complicated, than that of the E-Girl Adrift. Instead of binging on social media, like Oyler’s narrator (a journalist who “spends all day on Twitter, ostensibly looking for stories but mainly just looking”), Dorothy spends a great deal of time thinking—and not, as the E-Girl Adrift might, to come up with contrarian takes for late-night internet brawls.

One can imagine a very boring version of Smallwood’s novel in which Dorothy spends her days scrolling through “Academic Twitter” (a profuse, often catty Twitter community in which academics share research and gossip), stalking former members of her PhD cohort and posting erratically. Instead, much of the novel is given over to incidents in which Dorothy’s penchant for analysis—the trait that is supposed to set academics apart—seems to fail her. On the paintings of Hilma af Klint, the narrator notes: “She could have never written a paper about them. She could not think about them; she could only think near them.” Elsewhere, Dorothy reluctantly attends an “underwater puppet show” and finds herself compelled, yet unable to read it as narrative: the show was “a gentle, ongoing state of ups and downs that contained moments of illusory transcendence and ultimately built to nothing.” These reflections send Dorothy on a disjointed psychic journey. Perhaps the miscarriage has forced a reckoning: what is a miscarriage, after all, if not a refusal of narrative development? And then there are the larger, more ominous, systemic questions. What, Dorothy wonders, is the real allure of academia? Why has she devoted her life to this cul-de-sac of a career path?

What the academy promises—or has historically promised—is the expansiveness of a self-directed life, and the freedom to pursue odd, specific subjects down their narrow rabbit holes. What the “life of the mind” delivers, at best, is half a decade of library work, followed by undercompensated teaching assistantships and a postdoctoral job market so winnowed-down it is nearly nonexistent. There is a misconception that once, the academy was collegial and placid—scholars strolling quietly through trimmed courtyards, nodding at each other from carrels in the library. When universities morphed into the quasi-corporations they are today, scholarly communities became beset with competition, cliquishness, and nepotism—mirroring the capitalist institutions they claimed to oppose. In truth, universities have always been sites of exclusion: for women, for people of color, for certain ethnic groups. (My own alma mater had its first Black graduate in 1948, and first decided to admit women in 1969; its commitment to preserving a “Jewish quota” for students and professors meant that Albert Einstein was passed over for a faculty position.)

For the lucky few it welcomes, the university promises temporary comfort: a constant stipend; a respectable, if taxing, job. But in the humanities, academic work can be stultifying, exchanging the messy uncertainties of a text for nebulous theorizing, ridiculous jargon, and flat, arcane arguments. As Dorothy attests, academia takes “the most simple and innocent desires—to tell stories, and stories about stories—and ma[kes] them ugly.”

I am biased against academia in more ways than one. At one point in my life, like Dorothy, I lived for the feeling—equal parts frustrating and exhilarating—of diving into the archives, poring over intricate works of theory, digesting everything I’d read (and only vaguely understood) into long, unwieldy papers. (Looking back on these today is a bit like looking at pictures of myself in middle school.) One passage, in which Dorothy attempts to read a monograph by the literary scholar Franco Moretti on a plane, reflects a situation I know only too well:

"I have read all of Stendhal in French, the book informed her nonchalantly. Dorothy nodded and proceeded to the useless labor of underlining the phrases 'objective historical demands' and 'significant for novelistic narration,' both of which were already italicized. I understand the internal logic of formal contradictions, the book added, straining to be heard over the chatter in the rows behind. Tell me again what you do?

"That’s not my field, Dorothy started to say, but the book talked over her."

In the academic world, it is not only professors and fellow students who will doubt your abilities. It is the field itself that will resist your efforts to conquer it, to absorb its complexities and tame them with fulsome, intelligent prose. You can always do more—read Stendhal in French, cram in more erudite references, find the perfect, obscure subject to entice a dissertation committee. If a professor comes too close, you let them—they might help you!—and hold back your distaste. (That Moretti is held up as the ideal academic here seems to me a sly commentary on the current state of affairs in Literary Academia; Moretti has been accused of sexual harassment by several former students.)

Even then, you might fall short. Dorothy’s graduate school nemesis, Alexandra, becomes a “rising star” in the department—outflanking Dorothy—by choosing to write her dissertation on “doors” in Victorian novels: “not what they were about—just that they were.” Here, as in many moments in the novel, Smallwood proves a pitch-perfect satirist: “What, Alexandra asked her fellow students in a teacherly tone, are the politics of doors?”

The politics of doors. I have heard many such phrases of bullshittery, and used them myself—proudly, without interrogating their meaning, or lack thereof. What were they hiding? What was I hiding, in those smug, baseless essays, so devoid of any kind of authentic feeling?

Perhaps, as Dorothy realizes on a trip to an academic conference in Las Vegas (not so far-fetched as a plot point; these conferences tend to be oddly ribald), the academic’s failure is one of perception. On her way back to the airport, she glimpses the famous replica of the Statue of Liberty:

"She was now thoroughly disoriented and had missed her opportunity to take in the replica statue as an aesthetic experience or form any coherent impression of it. It was behind her. To say her impression was in pieces would imply it was broken, when in fact, it had never been assembled."

The desire to interpret butts up against the unstoppable force of experience. Dorothy can’t “assemble” an impression or analysis of the statue because she is only witnessing it—letting its superficiality, its utter resistance to semiotic reading, wash over her. This is what academia prohibits by swapping perception, and the simple pleasure of merely experiencing, for percipience. Perversely, that exchange has the tendency to dull the mind. The world becomes inert and two-dimensional, a series of hieroglyphs to be compared to a key. If Dorothy is a failed scholar, her existence in academia “useless” and “abject,” she may be better off for it.

Those who can’t do, teach, goes the common (and insulting) adage. Maybe there’s an academic corollary: Those who can’t write literature get a graduate degree in literature. Smallwood is a brilliant exception to that rule, and her novel—unusual, funny, and incisive—is a welcome corrective to a growing canon of literature about disaffected millennial women. Dorothy’s ironic sensibility never outstrips her humanity, and every chapter brings surprise and new dimension—a testament to Smallwood’s eye for narrative, and her generous, often luminous prose (blissfully free of academic bullshittery). “The triumph of the quantitative was to be resisted,” Dorothy muses at one point. “Wasn’t that the point of literature?” Maybe so, but I give this novel an A+.

Sara Krolewski is a writer and student living in the East Village. Get to know her better: @sarasara.sck

Thumbnail Image: Tree of Knowledge, 1913 (Oil on Canvas), by Hilma af Klint