by Holly Devon

Anytime you make casual reference to the fact that the CIA has their hands in everything from global media to modern art, it is likely that whoever you’re talking to will respond as if you are wearing a tinfoil hat and have offered to make one for them too. But as ludicrous as it may sound, the fact is that during the Cold War just about every major contemporary cultural gatekeeper you can think of was in bed with the CIA. The New York Times, Time, Life, and Newsweek magazines, The Wall Street Journal, and CBS and ABC News were among the 22 media outlets who employed CIA agents as journalists in the first decades of the Cold War. In the arts the list is even longer. Most notably, Martha Graham’s dance company, The Paris Review, the Iowa Writers Workshop, and the Museum of Modern Art were all funded by the CIA, with agents often filling key leadership positions.

The first time the CIA propaganda machine made headlines was in 1973, when it came to light that the CIA had three dozen agents on payroll that were working as journalists abroad. Then, in 1977, The New York Times series “The CIA: Secret Shaper of Public Opinion” revealed that the agency’s Propaganda Assets Inventory controlled over 800 publications worldwide.

The Propaganda Assets Inventory started in 1947, but it came into its own during Frank Wisner’s tenure as Director of Central Intelligence. Wisner had gotten his start at the agency in the Office of Policy Coordination, for which propaganda was first on the list of responsibilities. Under his direction, the agency’s narrative reach expanded into at least 35 countries. As the 1977 article put it, “The thread that linked the C.I.A. and its propaganda assets was money, and the money frequently bought a measure of editorial control, often complete control.” Agents liked to joke behind closed doors that the Propaganda Assets Inventory was “Wisner’s Wurlitzer,” a jukebox that with one touch of a button could play whatever tune the CIA director wanted to hear, anywhere in the world.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was the agency’s most prized possession in their far-reaching web of propaganda. The CCF founded the Paris Review, funded the Iowa Writers Workshop, and canonized Martha Graham’s style of modern dance. As historian Francis Stoner writes of the CCF in Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, “Whether they liked it or not, whether they knew it or not, there were few writers, poets, artists, historians, scientists, or critics… whose names were not in some way linked to this covert enterprise.”

Ardent Cold Warriors had always feared communism’s cachet in the international art community; communist artists were frequent targets of the CCF. When Chilean poet (and committed communist) Pablo Neruda was up for the Nobel Prize in 1964, the Congress for Cultural Freedom mounted an international campaign against him. Instead, they supported artists who took up the banner of “art for art’s sake,” rewarding those who severed the ties between art and politics with money and prestige.

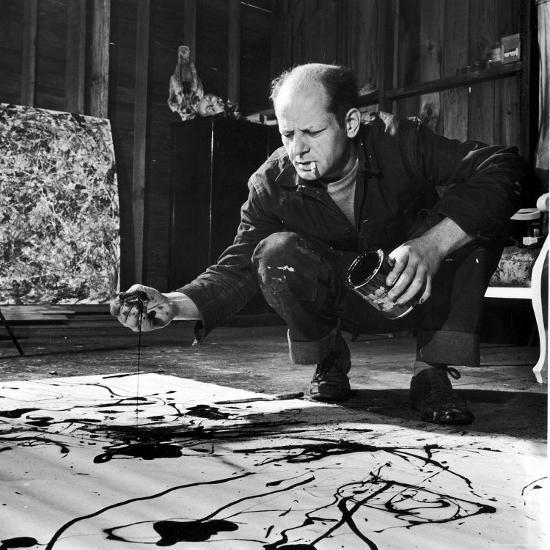

Contemporary art was the CIA’s pet project. The CCF organized and funded the first major Abstract Expressionist art shows: “Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century,” a 1952 art festival held in Paris, was a collaboration between MoMA and the CCF. CCF-funded magazines gave the featured artists glowing reviews. The Partisan Review, edited by Clement Greenberg and funded by the CCF, frequently championed the Abstract Expressionists. Greenberg was particularly vehement in his praise. As Louis Battaglia writes, “Greenberg produced a body of prose that single handedly claimed the mantle of modernity for the New York School of Abstract Expressionist painters. By the mid-1950s… the rest of the art world and general public had come to recognize the New York School as the successors to the Parisian School in defining and leading Modernism."

For years, those who doubted the rumored connections between modern art and the CIA wondered about the motive. What could the CIA have to gain by pouring money into the avant-garde? But in 2013, The Independent ran a story by Frances Stonor Saunders in which interviews with former CIA officers both confirmed the rumors and explained the connection. The CIA’s control of the artistic narrative was known as “Operation Long Leash.” By funding artists who made Western art seem daring and progressive (largely without their knowledge), the CIA hoped to control the narrative with such a light touch that no one would even know they were involved. Operatives like “Long Leash” case officer Donald Jamison undertook the project “at two or three removes,” according to the article, so that the agency would not have “to clear Jackson Pollock, for example, or do anything that would involve these people in the organisation.”

Essentially, the agency’s support of the arts was their way of taking out splashy ads for American capitalism. The Soviets kept their artists on a short leash, but in the United States, the leash was so long it looked like freedom. Just ask the artists: “I’m not a propagandist,” Martha Graham told anyone who asked on her dance company’s state-sponsored tour of what the government called “domino countries” (nations considered particularly susceptible to communism).

For Tom Braden, head of the CIA’s International Organizations Division (IOD), culture was a central stage in the Cold War theater. “I think it was the most important division that the agency had,” he said. Braden had IOD agents placed in film and publishing houses, and funded everything from jazz and American touring orchestras to a cartoon version of Animal Farm. But plucking avant-garde artists from the cultural margins and dropping them onto the international mainstage is perhaps Braden’s most significant accomplishment. In his interview for the Independent feature, he likened himself and the agency to the patrons of Renaissance art. “It takes a pope or somebody with a lot of money to recognise art and to support it,” he said. “If it hadn't been for the multi-millionaires or the popes, we wouldn't have had the art.”

Indeed, multi-millionaires played a crucial role in the strategy of using experimental artists like Jackson Pollock and Martha Graham as brand ambassadors for Western capitalism. "We would go to somebody in New York who was a well-known rich person and we would say, 'We want to set up a foundation,'” Braden said. “We would tell him what we were trying to do and pledge him to secrecy, and he would say, 'Of course I'll do it.’" The individualism of the avant-garde fit neatly into the American narrative of free market capitalism; Nelson Rockefeller, one of the IOD’s eager recruits, called Abstract Expressionism “free enterprise painting.”

After they were briefed by the agency, Rockefeller and fellow MoMA board member Julien Fleichmann quickly put MoMA to work propagating the narrative of American artistic exceptionalism. While working for the CIA, Braden himself held a position as MoMA’s executive secretary. The alliance between the CIA and high-profile multi-millionaires reinforces that what the United States was fighting for in the Cold War was not the nation-state, but capitalism writ large. From the outside, the money pouring into the New York-centered art scene seemed to validate the narrative of its elite patrons, whose approval quickly became a prerequisite for a career in the arts.

New York’s cultural domination had an effect that rippled out to the rest of the world. The global opportunities on offer from the new order were only extended to those who met its criteria for high art. In the “domino countries,” centuries-old artistic traditions were relegated to the categories of “crafts”, or at best, “folk art.” As historian Jean Franco writes, the Congress for Cultural Freedom offered “inclusion in the ‘universal’ culture, although this disguised a not-so-subtle attack on national, ethnic, and local cultures, which were denigrated as aberrant, merely provincial, or as idiosyncratic.” An artist that fell outside the lines drawn by the CIA may not have been sent to the gulag, but they would be sneered at or ignored, and left to languish in obscurity.

The CIA’s outsized influence on art and media is rather old news. By now, countless books have been written, articles circulated, and tweets tweeted on the subject. But the agency’s role in shaping 20th-century public opinion has yet to enter the mainstream discourse. Even though it's a longstanding, well-established fact that supposedly apolitical gatekeepers conspired with government propagandists, bringing it up in conversation (especially around artists) still makes you sound like a conspiracy theorist. All you can do to save face is pray the person you’re talking to looks it up.

Part of the problem is that trying to grapple with the agency’s cultural legacy can feel like shadow boxing. The elegance of the “long leash” strategy is that instead of the overt propaganda of the Soviet Union, the political subtext of “art for art’s sake” appears incidental, and by now, beside the point. These institutions and organizations have long cut their ties with the agency and now operate solely through private funding; they can now claim their CIA patronage is a thing of the past.

But the reputations of the “Long Leash” artists remain untarnished. In fact, if their work is any indicator, contemporary artists are actively discouraged from emerging from the shadow of their predecessors. After modernism begat postmodernism, a movement which left everyone so fatigued that the question of what constitutes art nowadays elicits a cynical shrug, the art world appears to have gotten stuck in an infinite modernist/postmodernist time loop. Blue-chip artists frequently churn out work that is almost identical to either the post-war New York avant-garde or the conceptual defecations of their progeny. Neither artists nor their public object, or even seem to notice.

The cultural supremacy of the elite institutions who prop these artists up goes similarly unchallenged, regardless of their disreputable pasts. If an artist lands a show at MoMA, they would be considered crazy to pass up the money and validation, and no art critic would be taken seriously for suggesting that collusion with such a politically regressive institution would in any way compromise an artist’s integrity. In the words of Protean Magazine’s Alexis Louis,“There’s no need for such a continuing effort by the CIA, because they’ve won. We’re now doing all the work for them.”

Our inability to question the judgement of our gatekeepers does suggest that however long the leash is, it remains firmly fastened around our necks. Even after undertaking an extensive investigation into the history of modernist propaganda in her Independent piece, Saunders stopped short of casting aspersions on the art itself, saying “it would be wrong to suggest that when you look at an Abstract Expressionist painting you are being duped by the CIA.” But would it be so wrong? If all the voices that initially legitimized those paintings had a hidden agenda, why shouldn’t the revelation of this agenda call into doubt the value of state-sanctioned art? For some people, standing face-to-face with a Jackson Pollock painting is not exactly an awe-inspiring experience. Gazing at his signature smudges of belligerent colors, there will always be those who wonder to themselves why it is that this paint-splattered canvas is worth $58.4 million. However, the relentless condescension of the art world towards those who don’t ‘get it’ has proven to be a very effective strategy for suppressing dissent; better to keep quiet than to be labeled a Philistine. For someone working in the arts, challenging modernist preeminence would be career suicide. But if it turned out our inner voices are onto something—that the whole circus is actually just a CIA ploy—wouldn’t that be a bit of a relief?

For Iowa Writers Workshop alumnus Eric Bennet, the answer appears to be a resounding yes. Bennet came to Iowa crackling with literary ambition, he details in an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education. He wanted to write “a novel of ideas, a novel of systems, but one also with characters, and also heart—a novel comprising everything.” Instead he watched with horror as the workshop slowly undermined his ambitions, cutting away at his creative instincts as if with hedge clippers. Through ridicule and disdain, the program pressured him into writing in one of three “small-is-beautiful” Iowa-approved literary styles. They demanded he accept that no good novel could be built on ideas, and that to aspire to greatness was cringeworthy. Access to the infinite realm of the cosmos was barred, leaving nothing but quotidian details and finely tuned grammar. As Bennet puts it, “The workshop was like a muffin tin you poured the batter of your dreams into. You entered with something undefined and tantalizingly protean and left with muffins.”

Shaken, he left Iowa with a suspicion that there was something sinister about what had just happened to him; he decided to investigate. “This aversion to novels and stories of full-throttle experience, erudition, and cognition—the unspoken proscription against attempting to write them—was the narrowness I sensed and hated,” he writes. “The question I wanted to answer, as I faced down my dissertation, was whether this aversion was an accidental feature of Iowa during my time, or if it reflected something more.” When his graduate research yielded the discovery of Iowa founder Paul Engle’s ties to the CCF and the Cold War theater, it was proof that his inner voices had not led him astray.

As literature abandoned the world of ideas, its departure was not lost on all observers. In his 1996 essay “Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky” (written after a full immersion into both Dostoevsky’s fiction and four volumes of his iconic biography), David Foster Wallace points out the stark contrast between passionately ideological Russian novels and the ironic and apolitical fiction written by the American novelists of Wallace’s generation. “The thing is that Dostoevsky wasn’t just a genius — he was, finally, brave,” Wallace writes. “He never stopped promulgating ideas in which he believed. And he did so not by ignoring the unfriendly cultural circumstances in which he was writing, but by confronting them, engaging them, specifically and by name.”

Dostoevsky’s writing made the writing of Wallace and his peers seem feeble, but Wallace admits that were an author of his time (presumably himself included) to tackle cosmic and political themes with Fyodor’s uninhibited fervor, “the novelist would be — and this is our own age’s truest vision of hell — laughed out of town.” Confronted with such visceral prose, he says, “any serious American reader/writer will find himself driven to think hard about what exactly it is that makes so many of the novelists of our own time look so thematically shallow and lightweight.” Trapped in this postmodern haze, he wonders, how can an artist find the courage it takes to be sincere—“how even, for a writer… to get up the guts to even try?”

Like Wallace, this writer started on her quest to find the meaning behind our country’s creative stagnation out of love for Dostoevsky. When I first encountered the mad Russian I was a frightened, weird, and lonely adolescent, and his wild, visionary books helped me make sense of my chaotic world. You might go into Notes from the Underground thinking high school is the most humiliating thing that can happen to a human being, but it only takes a few pages for Dostoevsky to disabuse you of that notion; Dostoevskian humiliation is simply made of stronger stuff.

Around the same time, I also started reading the National Book Award winners pressed into my hands by well-meaning adults. Instead of illuminating the world, they made me feel confused and ill at ease. I remember reading Michael Ondaatje one summer and poring over his writing, trying to figure out why something so elegantly wrought could leave me cold. I couldn’t fathom why books written by prize-winning living authors made me feel even lonelier than I was before, while all my favorite dead authors gave me back my will to live, their books offering the strength and clarity I needed to find my own path. Reading Wallace’s essay years later, it was startling to see a card-carrying member of the literary elite grapple with the same questions. When he asked “who is to blame for the philosophical passionlessness of our own Dostoevskys?”, I felt I needed to know the answer.

Now, as an adult writer eking out an existence in a materially impoverished but spiritually dazzling city that New York elites both exoticize and dismiss as a cultural backwater, I finally do. But knowledge of the CIA’s involvement in the creation of the listless and spiritually bereft morass that drains each successive generation of its creativity and life force doesn’t tell us how to escape it. These days, placing oneself ideologically outside the center of cosmopolitan culture is to live in irrelevant exile.

How can we act on the information that our cultural ecosystem is a conspiracy of frauds when it is now almost impossible to make it as an artist who goes against the grain? “The prospects are not very encouraging,” Edward Said admitted in 1999, upon observing how thoroughly the CIA’s cultural interventions have blocked our exits. If censorship was bad then, it seems to only have gotten worse. “Fin-de-siècle globalisation is a stickier, more encompassing element for the intellectual to function in than the Cold War,” he contended. Now, as housing prices and costs of living continue to rise precipitously, defying the established narrative is practically risking starvation.

But I find comfort in the knowledge that this struggle is nothing new. Fighting state control is part of the artist’s job description, and anyone who forgets it is either painfully naive or willfully ignorant. As James Baldwin writes, “the nature of the artist’s responsibility to his society... is that he must never cease warring with it, for its sake and for his own.” If that war pushes us into the margins, then so much the better; there, artists are fighting on home turf.

“The war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war,” Baldwin explains, “and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real.” As much as the CIA exhausted the word “freedom” during the cultural Cold War, the agency never could glimpse its meaning. Whether the state dangles the carrot or swings the stick, it is fighting desperately against the power of the truth—and for good reason. This generation has a ways to go before we successfully wield that power, but there’s no denying the glory to be won by those who try.

Holly Devon is a writer and editor based in New Orleans. Get to know her better: @Holly_devon7

*Thumbnail image of Jackson Pollack working in his home studio by Martha Holmes, 1949.